Back in May, there was a flurry of announcements from websites and social networking apps in China indicating that they would be suspending their interactive features – such as basic comment functions and so-called “bullet comments” proliferating across video in real-time – in order to carry out “upgrades.” In some cases, the suspensions were by all accounts permanent.

Users in China were quick to pick up on the fact that these were not at all about improving services, but rather pointed to a concerted effort by internet control authorities to restrict interactivity for the sake of convenience in exercising control over public opinion.

The same sorts of suspensions had already been happening in April, likely in response to the approach of sensitive historical anniversaries, like the centenary of the 1919 May Fourth Movement, the 30th anniversary on April 15 of the death of reformist party chief Hu Yaobang, and of course the 30th anniversary of June Fourth.

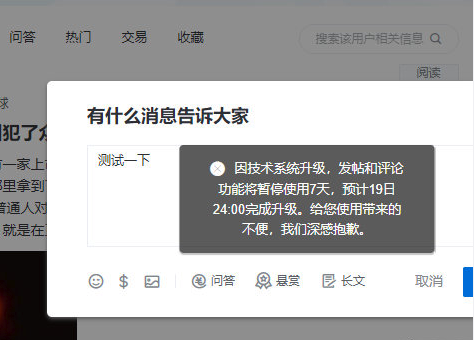

The suspensions were likely extensions of a special cleanup campaign announced in January this year by the Cyberspace Administration of China, aiming to “resolve outstanding problems in the online climate.” Commenting in one chat thread on April 12, as someone asked about the seven-day suspension of commenting functions at Snowball (雪球), an investment information platform, one user said: “Technical upgrades are just an excuse; this is actually about speech prohibitions.” In some cases, public notices were made of suspensions with express mention of violations of China’s Cybersecurity Law and Regulation on Internet Information Service — as was the case with Jianshu (简书), a user-generated content platform similar to Medium, which in April underwent “a full and comprehensive rectification (全面彻底的整改) of its content starting April 19.

A number of sites and services announced in mid-May that suspensions of interactive features such as comments would last between several weeks and three months. On May 10, the Ding Talk (钉钉) mobile communication app, developed by Alibaba, and the Momo instant messaging app both issued notices saying that their “friend chat” services resembling the chat services offered by WeChat would be suspended for upgrades.

The animation-themed video site Bilibili (哔哩哔哩), which has been extremely popular, also announced that it would suspend “bullet comments” on its video service from May 29 to June 6. Tencent also reported in May that other services, including YY, Douyu (斗鱼) and Huya (虎牙) had suspended “barrage” comments.

On May 27, Qdaily (好奇心日报), a site offering current affairs and lifestyle content, much of it translated or summarized from foreign sources, announced that its website and app would suspend content refreshing from May 28 for a period of three months. During this process readers were encouraged to read existing content, the site said.

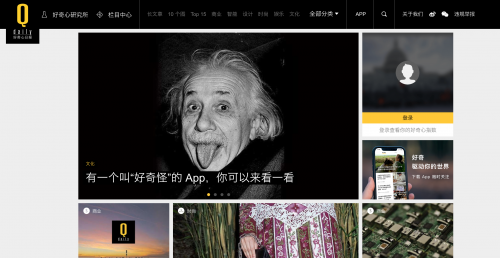

To get a clearer idea of just how disruptive these controls can be for media like Qdaily, just try visiting their site and having a look for yourself. Here is the site’s front page on June 21, three weeks into their suspension.

The headline under Einstein reads: “There is an app called ‘Very Strange’, come and see.” Click into the article and you find it is dated May 27, 2019. Another featured article, dealing with bluetooth earbuds, dates back to May 24.

Right below the feature slider, with its black-and-white image of Einstein, is the announcement of Qdaily‘s suspension, the publication’s logo set against a sunset backdrop. There is no talk of “illegal information,” or the need for a clean “online ecology.”

The notice, just four lines, reads:

From midnight on May 28, the Qdaily website and App will suspend content refreshing for 3 months.

During this time readers can enjoy our past content.

Reader comments and other interactive services will be suspended.

Interactive features for Qdaily Research will appear in another App called ‘Very Strange,’ and readers can participate there.

There is no indication in the notice that Qdaily is facing anything at all serious. Nothing fatal, at any rate. But how is that even possible? How can any for-profit media venture simply live in cryo-freeze for a period of three months and then wake to the world again as a viable source of information?

In decades past, it was impossible in China to kill a publication or render it comatose without some degree of uproar. Just think of the international stink that ensued in 2006 when authorities ordered the shutdown of the respected Freezing Point supplement of the China Youth Daily newspaper.

But for propaganda controls, this is indeed, as Xi Jinping is so fond of saying, a “new era.” These days, an interesting, vibrant and cool platform like Qdaily could simply walk off into the sunset, without a fuss and without so much as a goodbye.

And who really cares? After all, there is always something new.