Chinese state media reported last month that foreign ministry spokeswoman Hu Chunying (华春莹), shown above, had said on July 26 concerning affairs in Hong Kong: “I advise those people who want to invite wolves into the house make a good reading of history. Throughout history, those who colluded with external forces to damage the country and cause suffering to the people — how many of them ended well?”

In just one short remark, Hua made use of two idioms — ”letting wolves into the house” (引狼入室) and “damaging the country and causing suffering to the people” (祸国殃民). The meaning of the first one, essentially to invite trouble, is clear enough, and dates back to the Yuan dynasty. The second, however, may be less familiar to younger Chinese, though for people of their grandparent’s generation, who grew up in the midst of the Cultural Revolution, it is only too familiar — even if has been a long time since they last heard it.

We decided to accept Hua’s challenge and look back into the history of this phrase, because in fact the way Ms. Hua was using it seemed a bit different from what we knew, and it wasn’t altogether clear she was in fact using it properly.

In the Republican Era, in fact, both the governing Kuomintang Party and opposition political parties used the phrase “damaging the country and causing suffering to the people” (祸国殃民) to launch attacks on one another. In 1917, the provisional government of Sun Yat-sen (孙中山) used the phrase to attack the Beiyang Government. And during the Anti-Japanese War, the phrase was used by the Nationalist government, by the Chinese Communist Party and by the Provisional Government of the Republic of China, the puppet state in Japanese-occupied territory.

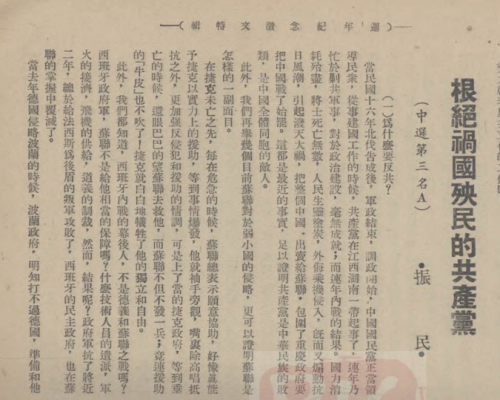

Here is an article in China Monthly from 1940, for example. The headline reads: “Rooting Out the Chinese Communist Party that Damages the Country and Causes Suffering to the People” (根绝祸国殃民的共产党).

After victory in the Second Sino-Japanese War, Chen Gongbo (陈公博), the Chinese politician who had been head of the Japan-backed provisional government in Nanjing, was put on trial, and many reports in the media used this phrase to refer to Chen. He in fact had been one of the founders of the Chinese Communist Party and a delegate to its First Congress. He underwent numerous shifts in his lifetime, and for a time under the Japanese wielded immense power. He was finally executed in 1946 after being extradited from Japan by American occupation forces after Japan’s surrender.

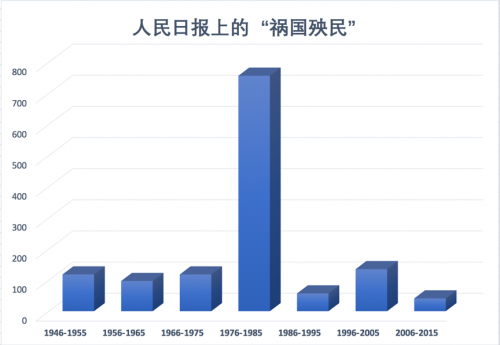

It was that same year in fact that the People’s Daily was launched. If we look at the occurrence of the phrase “damaging the country and causing suffering to the people” in ten-year periods throughout the newspaper’s history, here is what the pattern looks like:

Notice the clear peak in use of the phrase from 1976 to 1986. What was happening during that 10-year period ito cause the phrase to rise so dramatically? I wonder if people my age remember.

During the first three 10-year periods shown above, use of “damaging the country and causing suffering to the people” was rather low, at about 11 or 12 articles per year. Generally, the phrase was used to attack the Kuomintang which had fled to Taiwan, and the governments of Western nations. During the same period we can also find “damaging the country and causing suffering to the people” in newspapers in Taiwan — used, as you might guess, to criticize the Chinese Communist Party.

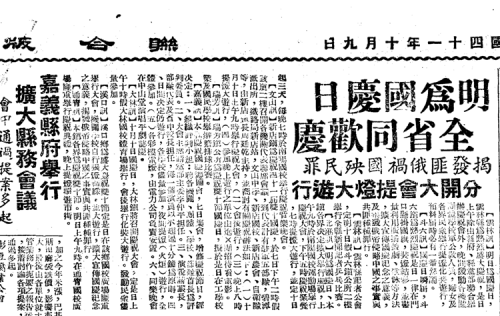

Below is a copy of Taiwan’s United Daily News from October 9, 1952, which uses “damaging the country and causing suffering to the people” in the headline:

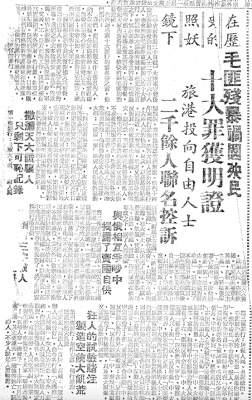

Between 1958 and 1962, Mao Zedong’s Great Leap Forward became an unmitigated disaster for China, resulting in the death of millions. Here is another page from the United Daily News, this time from October 1, 1963:

The report refers to Mao Zedong as a bandit “damaging the country and causing suffering to the people,” and includes eyewitness accounts provided by Chinese who left the mainland in 1949, and from others who fled through Hong Kong in 1962. The small headline for the article reads: “A Madman’s Experimental Gamble, Creating an Unprecedented Famine.”

Just a few years later, in 1966, the Cultural Revolution unfolded in China, unleashing a new wave of misery. Chiang Ching-kuo, the eldest son of Chiang Kai-shek, who at the time was Taiwan’s Minister of Defense “called on the enslaved youth of the mainland to turn their guns and eliminate Bandit Mao, who has damaged the country and caused suffering to the people.”

When Mao Zedong died in 1976, Taiwan’s newspapers again used the phrase. Mao was the great destroyer, the criminal who had “damaged the country and caused suffering to the people.”

In China, Mao Zedong’s death was the closing of a long period of tragedy. Not even a month after Mao had passed, the “Gang of Four,” which included Mao’s wife, Jiang Qing (江青), was arrested. Anger over the excesses of the left erupted, and a campaign of denunciation of the “Gang of Four” rolled across the country. On October 22, 1976, the People’s Daily published a poem by Xu Gang (徐刚) called “Forward, Mother Country” (祖国,在前进), which rang like a lofty slogan:

Strike down these conspirators who oppose the Party’s power;

Strike down these thieves who damage the country and cause suffering to the people!

It was during the movement against the “Gang of Four” that the phrase “damaging the country and causing suffering to the people” reached the peak we see in the graph I shared at the start. In the period from October 1976 to the end of 1977 alone, the phrase was used in 512 articles in the People’s Daily.

The trial against the “Gang of Four” lasted from late 1980 into early 1981, until all members were finally sentenced. Here is the front page from Taiwan’s China Times on January 26, 1981:

One headline on the reads: “Counting the Bloody History of the Cultural Revolution! A Decade That Damaged the Country and Caused Suffering to the People.”

It was at this point that both the Kuomintang and the Chinese Communist Party, on their respective sides of the Taiwan Straits, actually came together at the level of discourse, both using the same phrase to point to the immense tragedies that had unfolded during the Cultural Revolution, during which, all could agree, disastrous policies had “damaged the country and caused suffering to the people.” The common target of this outrage was the “Gang of Four,” but of course everyone knew that the real culprit was Mao Zedong.

When people of China’s older generation hear the phrase “damaging the country and causing suffering to the people,” this is the history that comes to mind. And this is of course why we see the frequency of the phrase rising dramatically in the 10 years following the Cultural Revolution.

The history of the phrase points to a very clear pattern of use, and it’s no surprise to find basic sources like Baidu Baike (百科) defining the derogatory phrase as being “most often applied to people or groups in power.” In this sense, Ms. Hua’s use of the phrase is actually unorthodox, though she is claiming to teach everyone a history lesson. One could say she is directing her fury at a “group” (集团), I suppose, but she is not directing it at those in power. We should remember, perhaps, that the Kuomintang, which was in power during the Second Sino-Japanese War, repeatedly criticized the Chinese Communist Party as having “damaged the country and caused suffering to the people.”

We should assume that a spokeswoman for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs has quite a strong team of writers behind her, assisting her with matters of phrasing. And yet, in this case, we must ask ourselves whether her use of the phrase “damaging the country and causing suffering to the people” is actually sufficiently precise — or whether its use in this context might have been a bit excessive.