China Newspeak

Tracing the “People’s Leader”

Earlier this month, CMP looked at the recent resurgence of “people’s leader,” or renmin lingxiu (人民领袖), in China’s official Party media as a term signaling the strong position of China’s top leader, Xi Jinping. We showed how the term, which first emerged in reference to Xi in April 2017, peaked briefly in the first half of 2018 before waning again – most likely as a reflection of the difficulties facing China in the midst of the trade war with the United States.

Students of Chinese political discourse will know that the term “people’s leader” was used to refer to Mao Zedong, and it still has a strong association with Mao’s rule. But where did the term actually originate in Chinese?

We took a brief jaunt back through available digital media archives to see if we could answer this question, beginning our search in the People’s Daily, which CMP co-director Qian Gang has referred to as the Chinese Communist Party’s “dictionary of red speech” (红色词典). First published on May 15, 1946, the newspaper can provide a fairly clear indication of how and when “people’s leader” was used in the history of the Chinese Communist Party.

In fact, we find that within its first week, on May 20, 1946, the paper published an article in which “people’s leader” appeared.

The article refers not to Mao Zedong, but to Ulanhu, the Mongolian Communist commander who secured Inner Mongolia for the Chinese Communist Party during the Chinese Civil War, and who during his career was nicknamed the “Mongolian King.” Ulanhu served as China’s vice-premier from 1956 until his purging at the outset of the Cultural Revolution in 1966.

In 1946, at the time of the People’s Daily article – which we should remember was more than three years before the founding of the People’s Republic of China – Ulanhu was known by his Chinese name, Yun Ze (云泽). The article reported on the formation of the autonomous regional government, and it called Yun Ze “the Mongolian people’s leader.”

Early uses of the term “people’s leader” in the People’s Daily indicate that its meaning was quite broad. The term could be used to praise figures past and present from all over the world. Among those referred to as the “people’s leader” in those early days, in fact, there was even American president Abraham Lincoln.

In Asia the title was used for Sanzō Nosaka, founder of the Japanese Communist Party, North Korean leader Kim Il-sung, North Vietnam’s Ho Chi Minh, and the Mongolian commander Khorloogiin Choibalsan. Europe had its “people’s leaders” as well. There was of course Stalin in the Soviet Union, Bulgarian communist leader Georgi Dimitrov, Poland’s Bolesław Bierut, Czechoslovakia’s Klement Gottwald, and Romania’s Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej.

It is true that “people’s leader” was used most liberally in the history of the People’s Daily to refer to Chairman Mao Zedong, with Marshall Zhu De coming in a distant second. But for Mao Zedong, the terms “people’s leader” and “great leader” (伟大领袖) were both used, and after the founding of the People’s Republic of China, “great leader” was the term most often applied to Mao. In Chinese political rhetoric, there is a greater sense of respect and power vested in “great leader” than in “people’s leader.” So against “great leader,” we find comparatively few references to “people’s leader Mao Zedong” (人民领袖毛泽东).

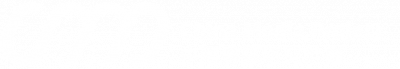

Before the founding of the PRC, we can find references to Mao as the “people’s leader” in other publications run by the Chinese Communist Party. Below is an article appearing in a magazine published by the Party in Shandong province in 1946, the headline reading: “The People’s Leader Loves Us Deeply.”

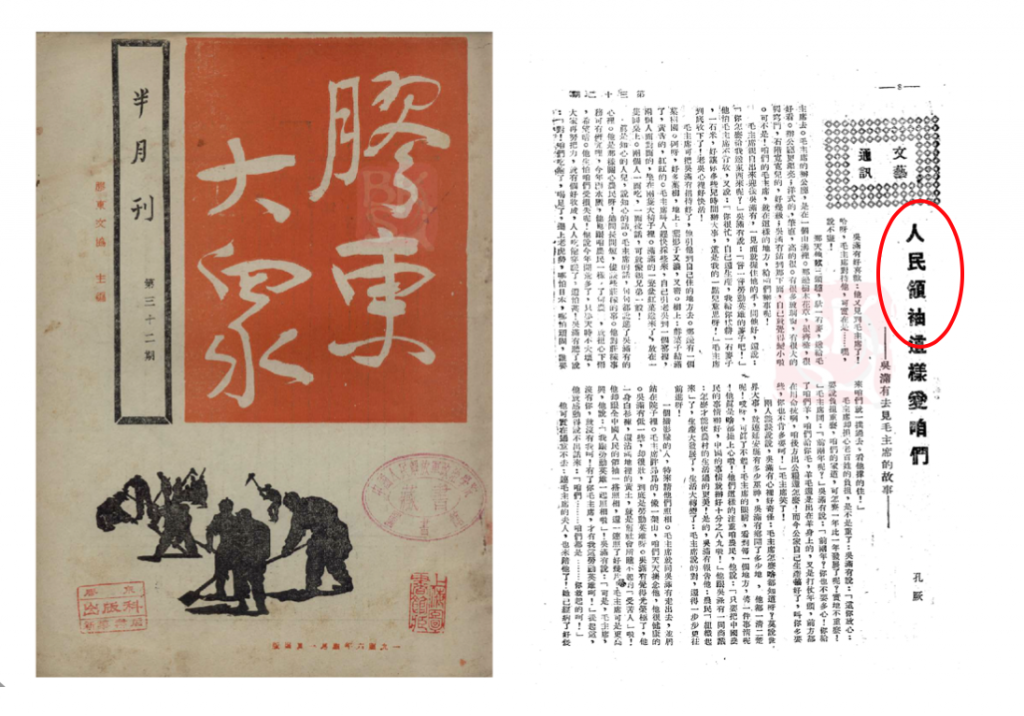

In 1948, the official magazine of the Huabei Military Region of the People’s Liberation Army also used the term, with a headline that read: “People’s Leader Chairman Mao.”

We can even find the term appearing in Hong Kong, as in the 1948 article below from the magazine Masses (群众), published in the then British colony by the Chinese Communist Party. “The Great People’s Leader,” the headline reads.

But to see how and when the term “people’s leader” might have entered the Chinese language, we need to go beyond the media and political culture of the Chinese Communist Party. So what about media from Taiwan and the Republican Era?

Looking further afield, we can find articles like this one in the June 3, 1955, edition of Taiwan’s United Daily News, which reports that a number of “anti-communist people’s leaders” had visited Taiwan. This use takes the term out of the revolutionary tradition (with Soviet echoes) of such leaders as Mao Zedong and Ulanhu.

Looking further back into media of the Republican Era, we can find other examples, like the following one dated to 1948 from Chinese-American Weekly, a magazine sympathetic to the Kuomintang Party that was published in New York. The headline you see in the article below refers to Nationalist military leader Fu Zuoyi as the “people’s leader.”

The Chinese-American Weekly article comes months before Fu’s secret December 1948 negotiations with the CCP.

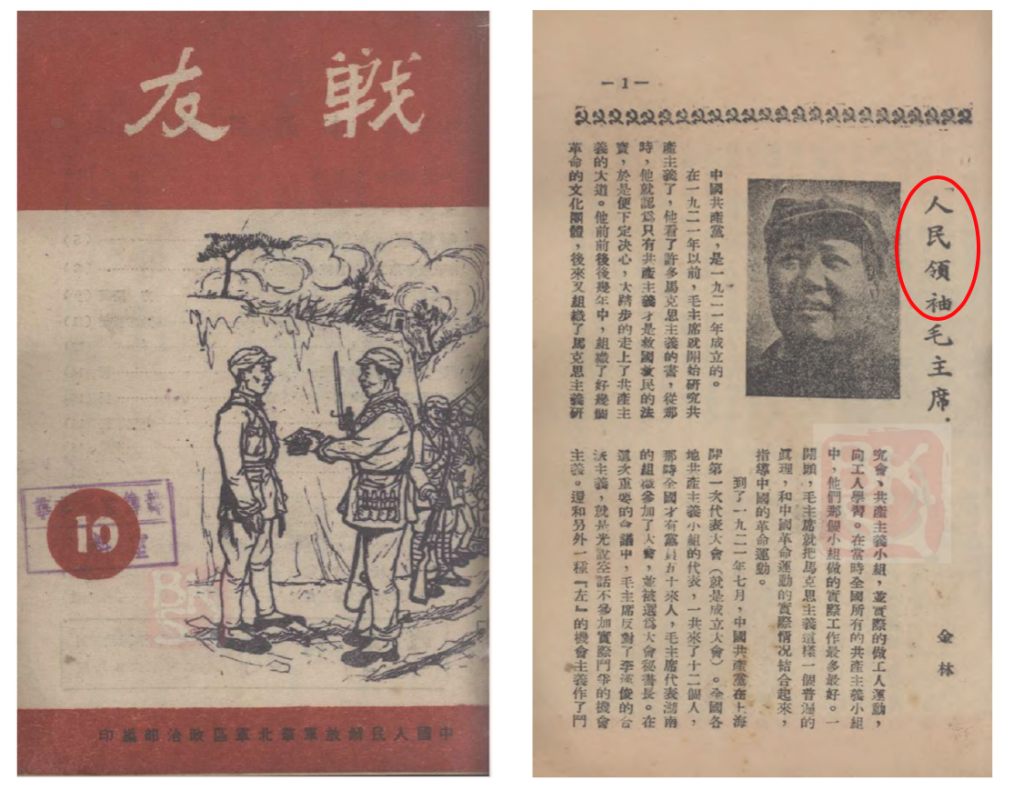

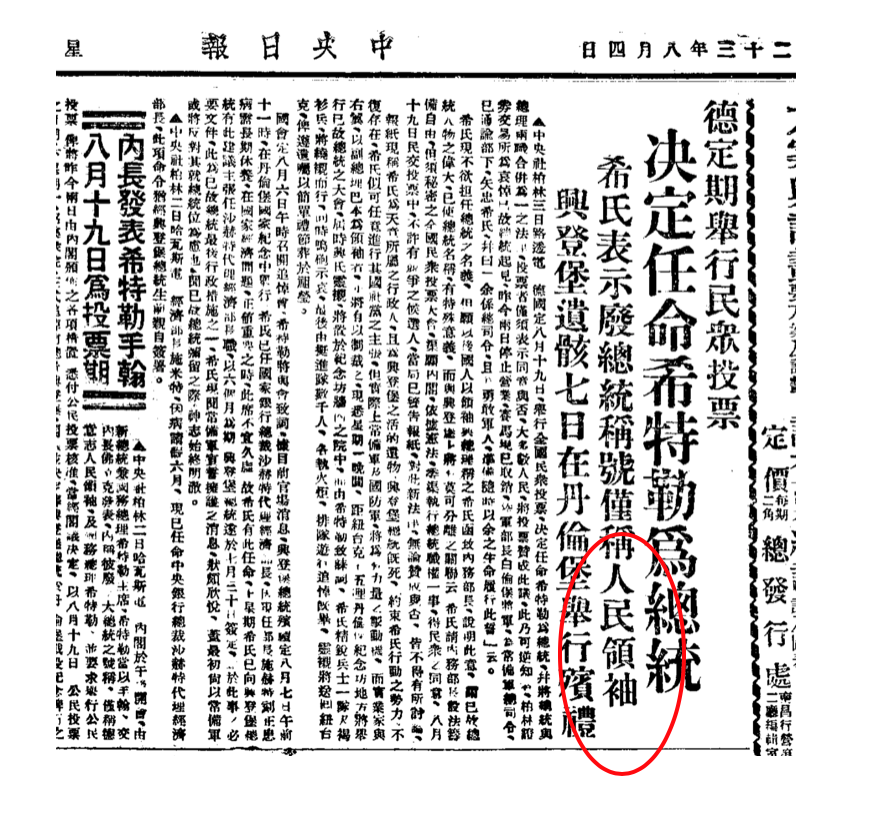

But the earliest example we could find of “people’s leader” in the Chinese language dates back to August 4, 1934, and appears in Central Daily (中央日报), a Kuomintang-run paper first published in Shanghai in 1924.

The news report that follows comes just three days after the death of German President Paul von Hindenburg, who had been Hitler’s only check on power, and reports that Germany is to hold a national referendum – referring of course to the August 19, 1934, referendum to merge the offices of president and chancellor, which would give Hitler supreme power.

The small headline immediately to the left of the largest headline reads: “Hitler Says He Will Drop Presidential Title and Be Called People’s Leader” (希氏表示废总统称号仅称人民领袖). This title, “people’s leader,” is familiar outside the Chinese language as the German word “Volksführer.”

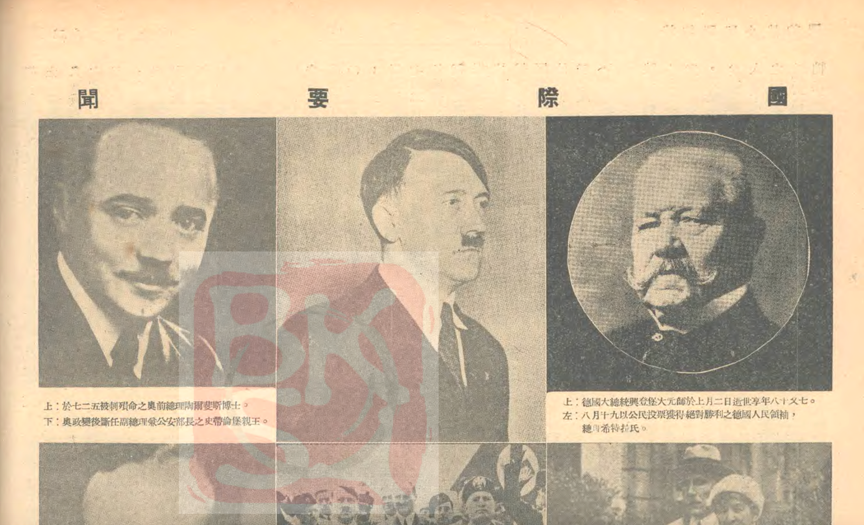

Shortly after the German referendum, Shanghai’s China Monthly (中华月报) reported the story and published a photograph of Hitler. The caption under the photograph read: “Achieving a decisive victory through referendum on August 19th, German people’s leader and chancellor Hitler.”

So it seems the earliest references we can find in digitally available Chinese-language media sources to the notion of the “people’s leader” are translations of the German “Volksführer” dating to Hitler’s rise as supreme leader. This is certainly not an etymology China’s present leaders would welcome, particularly given highly sensitive references in the social media space to “Xitler” (习特勒).

But the end of the digital trail is certainly not the end of the trail. In his study of the vocabulary used to describe authoritarian leaders in the 20th century, Russian historian Boris Kolinitskii noted that Russian lawyer and revolutionary Alexander Kerensky was referred to as “leader of the people” as early as March 1917, predating the personality cults and related vocabularies used for Lenin and Stalin.

In 1918, at a period when Lenin was busy consolidating power with his inner circle of Stalin and Trotsky his close confederates, Russian poet Osip Mandelstam wrote in “Twilight of Freedom“:

Let us praise the momentous burden

that the people’s leader assumes, in tears.

Let us praise the twilight burden of power,

its weight too great to be borne.

Li Yuzhuo (李玉贞), a historian specializing in the Soviet era, wrote for the journal Yanhuang Chunqiu about Yefim Alekseevich Pridvorov (pen name Demyan Bedny), the Soviet poet and satirist, as one of the earliest figures in Soviet literature to “fix the image” of Stalin, and perhaps the first to refer to him as “people’s leader” in the 1920s.

It makes sense that the term “people’s leader” would have currency within the political culture of the Chinese Communist Party as an import from the revolutionary tradition of the Soviet Union. One can imagine there must have been references to the “people’s leader,” drawn from Soviet newspapers and from contemporary literature appearing in Chinese translation in newspapers, magazines and journals in the years around the founding of the CCP in July 1921 — references that were simply beyond our fingertips for this brief search.

In any case, while the term “people’s leader” has appeared in various contexts throughout its history in the Chinese language — even in reference to Abraham Lincoln, various Asian leaders and Republican anti-communists — its century-long association with authoritarianism and the personality cult should be clear. This is the history that rattles the nerves of many Chinese, both inside and outside the Party, who caution that the line was drawn back in 1982 when the Party’s Charter was amended to prohibit personality cults.

We don’t yet know of course whether Xi Jinping will work to further blur the lines, or cross them. For now, it seems, he is attempting to consolidate his image and position around the notion of the “people’s leader,” the term’s history hidden to most. If he can manage to consolidate this position and title, could Xi Jinping reach for greater rhetorical and real heights — like status as “great leader”?

The history of CCP political discourse shows us that titles and honorifics can be difficult to hold.

A quick search of “people’s leader” over the past week suggests Xi might not even be holding this title in the short term. One of the only references to the term in the past week comes from Tianjin, which seems to be one of the most vocal local leaderships in support of Xi. In his speech to the third plenum of the municipality’s 17th local congress, Party Secretary Li Hongzhong (李鸿忠) spoke of “bathing in the warm sunshine of the care of the people’s leader” (沐浴着人民领袖亲切关怀的温暖阳光).

In an era of digital information, how effectively can such echoes of the past century be sold to savvy and often cynical consumers? We shall have to see.