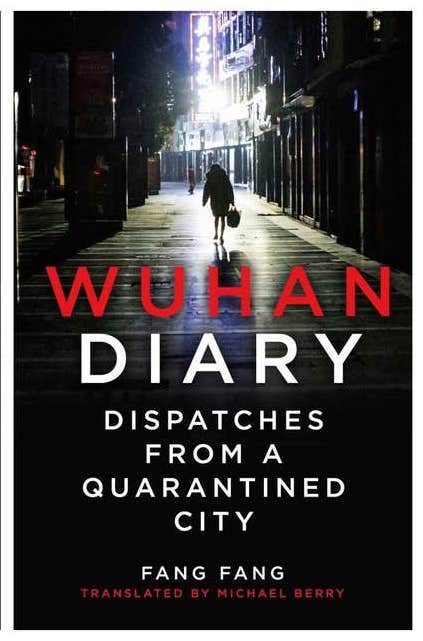

On June 10, the website China Military (chinamil.com.cn), a news portal operated by the People’s Liberation Army, ran an attack piece on the author Fang Fang, whose diary documenting 74 days under quarantine in Wuhan during the coronavirus epidemic was recently published in both English and German editions. Fang Fang’s Diary, in English titled Wuhan Diary: Dispatches from a Quarantined City, is an insider’s account of events in the city of Wuhan, the epicenter in January this year of what would eventually become a global pandemic, and it offers details about the crisis and the official response that are highly embarrassing for China’s leaders.

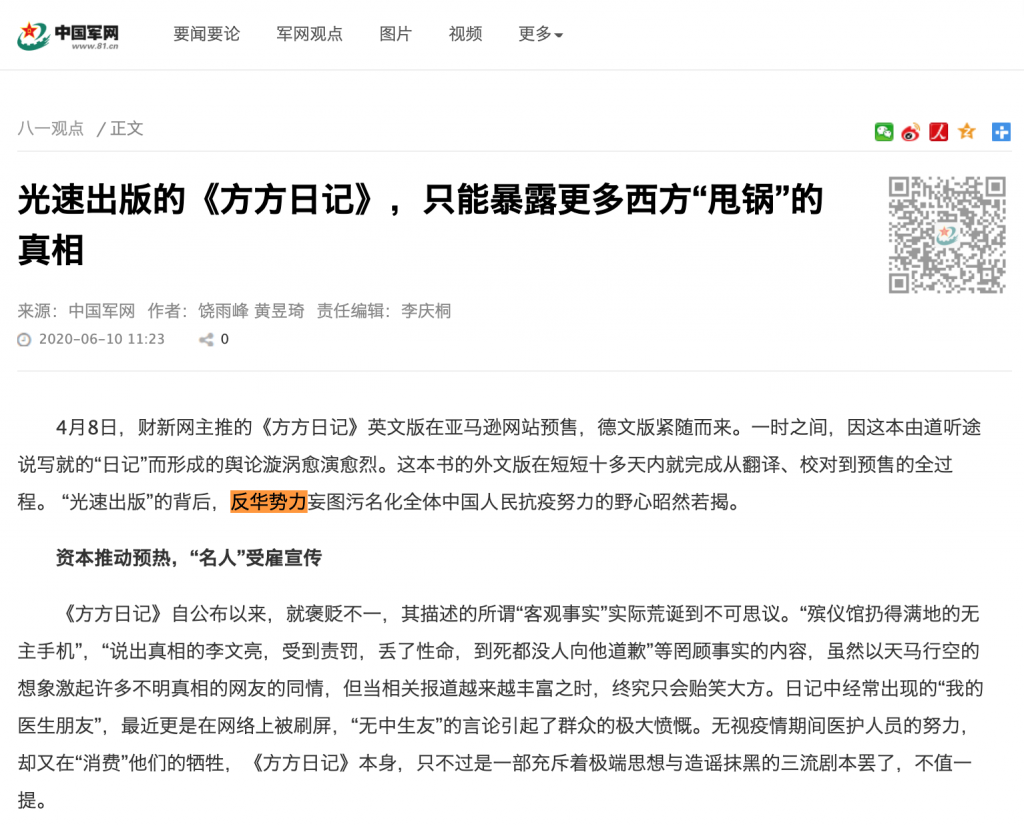

The piece at China Military, “The Lightspeed Publication of “Fang Fang’s Diary” Will Only Expose the Truth About More Western “Pot Throwing, alleges that certain “bad domestic media,” principally Hu Shuli’s Caixin Media, are responsible for pushing Fang Fang’s account and making it a tool for critics of China in the West.

The term “pot throwing,” or shuǎiguō (甩锅), which originated online in China, is roughly equivalent to the English phrase “shifting the blame.” The suggestion in the article is that unspecified “forces” in Europe and North America wish to use accounts like that of Fang Fang to blacken China’s name over the Covid-19 epidemic in order to direct attention away from the worsening situation in their own countries in terms of coronavirus infections and the epidemic response.

The article begins:

On April 8, the English edition of Fang Fang’s Diary that was promoted chiefly by Caixin Online began online sales on Amazon, and the German-language edition followed closely behind. Overnight, the public opinion maelstrom caused by this “diary” based on hearsay grew more and more fierce. The entire process of translation, proofreading and sales of the foreign language edition of this book was completed within just over 10 days. Behind this “rapid publication” are the obvious efforts of anti-China forces attempting to stigmatize the anti-epidemic efforts of the Chinese people.

The key allegations in the article are five-fold. First, that Fang Fang’s Diary is hateful toward China and therefore an “anti-Chinese” work. Second, that Fang Fang’s Diary was “promoted chiefly” by Caixin Online, suggesting that this widely respected news outlet bears responsibility for the attention given to the work to begin with. Third, that the “lightspeed” effort to translate the book reveals that it is an attempt by “anti-China forces” to call into question the efforts of the Chinese people to fight the epidemic. This third point is really about what is now a key message in much propaganda in party-state media – that the CCP’s response to the epidemic was an unalloyed victory. Fourth, the article disparages and seeks to discredit Fang Fang’s work as third-rate and little more than gossip.

Finally, beyond its attack on Caixin, the article suggests other domestic media were complicit. Here is a translation of the relevant passage in the piece:

Who could have guessed that this third-rate stage script could prompt such fierce attention domestically and overseas, something that is inseparable from the hyping and promotion done by certain bad domestic media. These bad domestic media promoted Fang Fang’s Diary through Weibo and apps, and even intentionally ran partial translations of Fang Fang’s Diary and interviews with the author on foreign websites, and the editor-in-chief even for a while promoted it once every day, fearing that traffic wasn’t yet sufficient, that things weren’t yet sufficiently chaotic.

It is never clear in the article what other domestic media or websites are being referenced by this charge levied at “certain bad domestic media” (国内某些不良媒体). But the reference to the “editor-in-chief” is clearly a shot taken at Caixin Media founder and editor-in-chief Hu Shuli (胡舒立).

Such open attacks on domestic Chinese media are rare. One of the last such attacks occurred in 2008 ahead of the Beijing Olympics and in the midst of unrest in Tibet, as more liberal media in China were attacked in commentaries and online as being unpatriotic for expressing more nuanced views on Tibet. At that time, Chang Ping (长平), a well-known editor at Guangzhou’s Southern Metropolis Daily, was roundly criticized for reacting to anger in China over the alleged bias of news outlets like CNN by pointing out the hypocrisy of Chinese state censorship.

Fang Fang’s Diary was first published as a series of blog posts at Caixin Online from January to April, with a total of 61 posts, most coming in February and March when the crisis was at its peak. In one entry translated into English at Caixin Global, Fang Fang cricticizes the suggestion by leaders in official propaganda that the Chinese people should be thankful to the government:

A word that crops up frequently in conversation these days is “gratitude.” High-level officials in Wuhan demand that the people show they’re grateful to the Communist Party and the country. I find this way of thinking very strange. Our government is supposed to be a people’s government; it exists solely to serve the people. Government officials work for us, not the other way around. I don’t understand why our leaders seem to draw exactly the opposite conclusion.