Xi’s Ten-Year Bid to Remake China’s Media

In recent years, the buzzword “media convergence,” or meiti ronghe (媒体融合), has abounded in official documents about public opinion and ideology in China. What does this term mean? And why is it important in a Chinese political context? The quick answer — it is about remaking information controls for the 21st century, and building a media system that is innovative, influential and serves the needs of the ruling party.

The idea of “media convergence” took off in official circles in China almost exactly 10 years ago as Xi Jinping sought to recast “mainstream media” (主流媒体) — referring narrowly in China’s political context to large CCP-controlled media groups, such as central and provincial daily newspapers and broadcasters — into modern communication behemoths for rapidly changing global media landscape. More insistently even than his predecessors, Xi believed it was crucial for the Party to maintain social and political control by seizing and shaping public opinion. To accomplish this in the face of 21st century communication technologies, built on 4G and eventually 5G mobile networks, the Party’s trusted “mainstream” media had to reinvent themselves while remaining loyal servants of the CCP agenda.

Xi Jinping saw an opportunity in the global phenomenon of media convergence, the interconnection of information and communications technologies, to consolidate the Party’s control over communication — so long as it could seize the initiative.

The New Mainstream

During a high-level meeting on “deepening reform” in August 2014, Xi Jinping set the course for media convergence with the release of the CCP’s Guiding Opinion on Promoting Convergent Development of Traditional Media and New Media. He urged the creation of “new mainstream media” (新型主流媒体), to be achieved through an ambitious process of convergence between traditional media and digital media. This would result in “new-form media groups” (新型媒体集团), he said, that were not just powerful and influential, but innovative.

The process that followed involved the creation at the both the central and provincial levels, and even eventually at the county level, of “convergence media centers” that focused on the application and integration of new tools and trends like big data, cloud computing, and blockchain at traditional media — but often focused on simpler things like the creation of digital content such as short videos and news apps to accommodate the mobile-first focus of media consumers. During a visit to the People’s Liberation Army Daily in December 2015, Xi Jinping noted that communication technologies were “undergoing profound change,” and demanded that media persistently innovate in order to maintain the advantage. “Wherever the readers are, wherever the viewers are, that is where propaganda reports must extend their tentacles, and that is where we find the focal point and end point of propaganda and ideology work,” he said.

More insistently even than his predecessors, Xi believed it was crucial for the Party to maintain social and political control by seizing and shaping public opinion.

Through 2017 and the CCP’s 19th National Congress, many local and regional media groups heeded the call, developing centers for multimedia content production and distribution, and investing in the necessary technologies. But as generally the case with such top-down policy programs, there was also significant waste and confusion about priorities. While a number of larger state-run media groups such as CCTV had the resources and market to sustain initiatives like “Central Kitchen” (中央厨房), a convergence center to produce a range of multimedia content for distribution through diverse CCTV channels, local governments that copycatted such methods found themselves saddled with unnecessary costs.

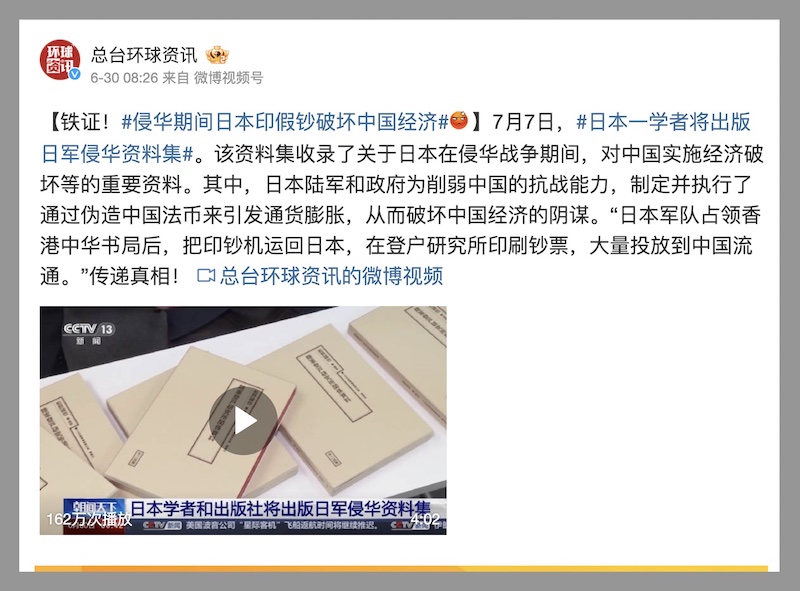

But the broader trend was unstoppable at all levels of the Party-state system, core to the Party’s vision of information control for the future. In September 2020, the General Office of the CCP and the State Council further accelerated the media integration strategy with the release of Opinion on Accelerating the Development of Deep Media Convergence. The Opinion pressed media groups across the country to actively innovate while keeping to the main direction of “positive energy,” a Xi Jinping-era term for emphasizing uplifting messages over critical or negative ones. From 2020 onward, official reports and analyses by CCP communication insiders routinely referred to media convergence as a “national strategy” (国家战略).

In February 2024, a report in the official Jiangsu journal Broadcasting Realm (视听界) to mark the 10-year anniversary of of the formal start to Xi Jinping’s campaign of “convergence development” (融合发展) noted 10 major accomplishments. These included the complete theoretical innovation of the Party’s public opinion and propaganda work and the systematic rollout of a consistent program of digital development, with innovations along the way. The result, the report said, had been the creation of a “modern convergence media system” (现代融媒体系) structured at the central, provincial, city and county levels. Media convergence was no longer just about “add ons” (相加), but had been implemented “from top to bottom.”

More concretely, the report noted the development and rollout of “Party apps” (党端), meaning state-run news apps targeting Chinese and foreign audiences, and a shift toward short video (短视频) to meet changing consumption patterns. In a telling sign of how media convergence was meant to consolidate CCP controls on information at the source, the report noted that the latest version of the government’s list of approved news sources — released in 2021, and naming those politically trusted outlets other media and websites were authorized to draw from without consequences — included official news apps as well as social media channels and public accounts.

Ten years on from the start of Xi Jinping’s media convergence campaign, the leadership seems confident it has wrestled back control of a media ecosystem that from the late 1990s through the 2000s had grown restive and unruly from the standpoint of public opinion controls. This has been aided by strict media controls under Xi Jinping, as well as the swift collapse of the traditional media models (such as advertising-driven metro tabloid newspapers) that to some extent empowered more freewheeling journalism more than a decade ago. Even if there have been cases of waste, particularly at the county level, there is also a clear sense that convergence has optimized the state’s use of media resources.

Going Global with Convergence

Over the past two years, China’s leadership has also sought to capitalize on a decade of nationwide media convergence to super-charge international communication. Released in May this year, a report on media convergence development in 2023, produced by a think-tank under the official People’s Daily, noted that the development of local and regional “international communication centers” (国际传播中心), or ICCs, has been “like wildfire” (如火如荼). These centers, which draw on the media convergence resources of provincial and city-level media groups and propaganda offices, are core to Xi Jinping’s effort to remake how China’s conducts external propaganda, the ultimate goal being to enhance the country’s “discourse power” (话语权) internationally, and offset in particular what the leadership sees as the West’s unfair advantages in global agenda-setting.

According to the People’s Daily think-tank, 31 ICCs were launched in 18 provinces and municipalities, including at the city level, in 2023 alone. According to our latest count at CMP, there are now 26 provincial-level ICCs in China.

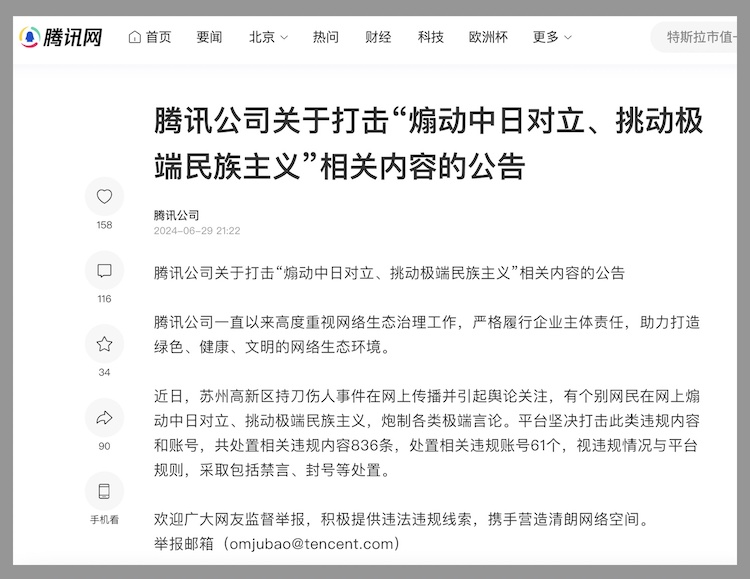

ICCs below the national level are now actively involved in producing external propaganda, much of it powered by the newest tool in the media convergence arsenal, generative AI, directed at foreign audiences through social media platforms such as Facebook, X, Instagram, YouTube and TikTok. Central state media and regional ICCs are working closely with state-backed technology firms to harness generative AI and streamline foreign-directed content production. Many of the media convergence centers that have sprouted up across the country over the past 10 years are now setting up centers dedicated to AI.

Ten years on from Xi Jinping’s August 2014 meeting on deepening reform, when the push for media convergence set off on the road to becoming a national strategy, the concept has become a crucial mixed bag in which the CCP leadership can pack its high-tech aspirations for information dominance, a core priority as old as the hills.

History has taught China's leadership that communication technology is a capricious force. More so, perhaps, than even at the dawn of the internet era in the late 1990s, drawing on the difficult lessons of the decade that followed, Xi Jinping is determined to pre-write the history of communication technology in the 21st century and its impact on politics at home and globally. If he succeeds, harnessing convergence media for the long-term benefit of the CCP's controlled system, this will no doubt be regarded — in the history "books" written by the Party's own generative AI — as one of the signature achievements of his New Era .