During a visit to the United Nations in September, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi launched a new international plan for AI development that focused on what has come to be called the “global south.” It was China’s resolve, Wang Yi announced, to work with other countries on data sharing and security, the production and supply of AI tech, building joint AI laboratories, educational exchanges, and creating an “open-source AI community.”

The release of the “AI Capacity Building and Inclusiveness Plan” (人工智能能力建设普惠计划) came on the heels of a UN resolution to strengthen international cooperation on AI tabled by China and a “core group” of partner states — and it positioned China as an alternative to the industry’s current leader, the United States.

In his speech on the plan, Wang emphasized that AI should be an inclusive and accessible technology. This was a not-so-subtle jab at the US, whose restrictions on high-tech exports have frequently been characterized in Chinese state media as a means not just to target the PRC but to assert its dominance over all other nations. “AI should not become a tool for maintaining hegemony or seeking advantages,” Wang said.

But the PRC’s actions suggest it may have ambitions of its own, grand if not hegemonic. The official People’s Daily newspaper has boasted that Wang’s AI plan “demonstrates China’s vision and responsibility as a major AI power.” Government rhetoric draws a direct line between AI exports and existing initiatives to expand China’s influence overseas, such as Xi Jinping’s signature Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and Global Development Initiative (GDI). In this case, the more influence China has over AI overseas, the more it can dictate the technology’s development in other countries.

Open-Access Development

Wang Yi’s speech, like other speeches on AI from Chinese representatives to the UN, echoed Xi Jinping’s directions on how the technology should be applied globally. In October, Xi launched the Global AI Governance Initiative at a high-level BRI meeting. In his speech, Xi framed the Initiative as an outgrowth of the BRI, and another means to create what he calls a “community of shared destiny for mankind.” The accompanying policy document outlines how AI should be “people-oriented” (以人为本) and a form of “intelligence for good” (智能向善). In other words, AI should be used to benefit humanity. It should offer solutions for global problems like social inequality and climate change, and must be kept out of the hands of malign actors.

The document also says that AI must not be used to interfere in another country’s internal affairs — language that the PRC has invoked for as long as it has existed, both to bring nations of the global south on board in China’s ongoing efforts to seize Taiwan and to deflect international criticism of its human rights record. The document also emphasizes that all countries should be able to harness the power of AI for their own development. AI, therefore, should be open access and free to all, with every country afforded equal opportunity to access the technology.

As Fu Cong, China’s special envoy to the UN, put it in his opening speech to the “Group of Friends” nations in November, AI must not “become a game for rich countries and rich people.” This is not just about the US versus China, in other words, but the West versus the rest.

China’s decision to co-launch its AI Capacity Building plan with Zambia also had a symbolic element. PRC state media reported that the African nation was the recipient of thousands of Chinese workers and hundreds of millions of RMB in loans in the 1960s, making it the beneficiary of one of China’s earliest overseas infrastructure projects — another thread connecting the latest in AI cooperation with China’s long-held ambitions to lead the developing world, even as it becomes a superpower in its own right. In a 2018 meeting with the Zambian president, Xi said they must jointly “safeguard the common interests of developing countries.”

AI Allies

There are a few possibilities for how this latest iteration of China-Global South cooperation could look on the AI front. One is through Large Language Models (LLMs). China is currently leading the way in open-source foundational LLMs — AI models that can be copied and altered for free by software developers, then used as the groundwork for them to build their own apps. Not only are Chinese LLMs cheaper than their Western equivalents, but they have also been reported by users to be more adept at handling East Asian languages and coding.

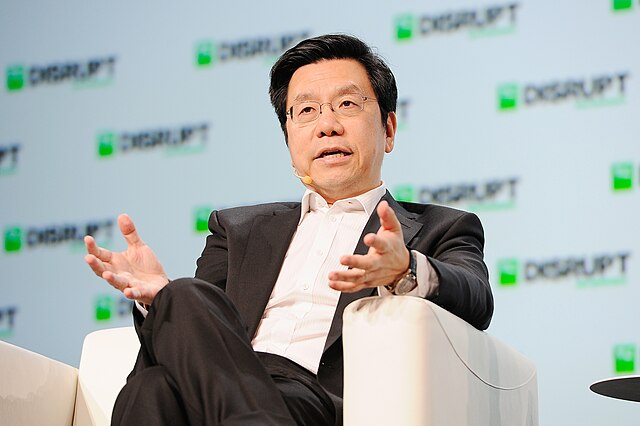

Leaders in China’s tech industry know that dominating this key software puts them in the pole position going forward. The founder of Chinese AI company 01.AI, Kai-Fu Lee, said at a recent industry summit that China can lead from a position of strength by mastering “large-scale model pre-training.” As long as their models are “good enough and cheap enough,” China will be positioned to determine “the bottom line of safety and controllability.” That could mean that, wherever they are in the world, they will have to conform to the CCP’s political redlines.

In some ways, this process has already begun. Egypt, one of the core members of the “Group of Friends,” has been expanding its AI program since at least 2019, collaborating with a number of different overseas companies to develop its AI capacity. In May, Huawei launched a public cloud service for the country, as well as the world’s first specialized Arabic LLM, which Huawei says uses “the world’s largest” Arabic dataset. In September 2022, Saudi Arabia also signed a joint venture agreement with Chinese AI company SenseTime (商汤) to create a localized AI lab.

As the strategic rivalry between the US and China draws much of the world into competing camps, AI is one key battleground in which the PRC is not merely “seeking advantage,” as Wang Yi put it in his high-minded speech at the United Nations, but has already found it.