In the latest case underscoring the persistent challenge of media corruption in China’s tightly controlled information environment, local district authorities in Shanghai reported this week that they had dismantled a “news extortion” (新闻敲诈) operation using a WeChat public account to blackmail companies for exorbitant “service fees” in order to make negative exposure disappear.

The case, authorities said, involved the exploitation of “supervision by public opinion” (舆论监督) — a concept that has typically been used officially in China to refer to the media’s power to expose malfeasance through reporting, with the proviso that this work does not directly criticize the Party. In this case, authorities allege, the WeChat public account in question exploited critical reporting to press companies into what were labelled “market promotion contracts.”

During the heyday of investigative reporting in China’s commercializing media in the early to mid 2000s, the phrase “supervision by public opinion” came to mean for some Chinese journalists something more akin to “watchdog journalism” in the West, with the idea of keeping power in check through reporting. Since 2012, Xi Jinping has moved to rein in these more professional and idealistic strains of “supervision,” emphasizing a more compliant and less oppositional approach in which “supervision by public opinion and positive propaganda are united” (舆论监督和正面宣传是统一的). Critical journalism has been radically restrained, even as the leadership has also stressed the need for internal supervision.

The Shanghai case follows patterns documented in previous alleged cases of news extortion across China.

On June 23, police in Qingpu announced the arrest of a suspect identified only as “Ding” (丁某), who operated a public account identified in official accounts as “X X Safety” (某某安全) — the name redacted, they said, for legal reasons. The account reportedly had 191,000 followers and daily views exceeding 8,000. After leaving his industry job in 2018, said an official release, Ding had leveraged his knowledge of the sector to establish the public account, which “initially focused on publishing industry-related company developments and analytical intelligence, accumulating a certain number of followers,” according to an official release.

Beginning in 2021, however, Ding was allegedly “no longer satisfied with objective reporting” (不再满足于客观报道), according to the police account. He deliberately sought “negative information” (负面信息) about target companies, then manipulated content, they said, through “clickbait headlines” (标题党), misattribution, and deceptive editing, colorfully referred to as “grafting flowers onto trees”( 移花接木). In one case this May, Ding published an article claiming a company had been shut down for illegal activities, then spliced in unrelated video footage from a separate criminal case in another province, creating false associations that damaged the company’s reputation.

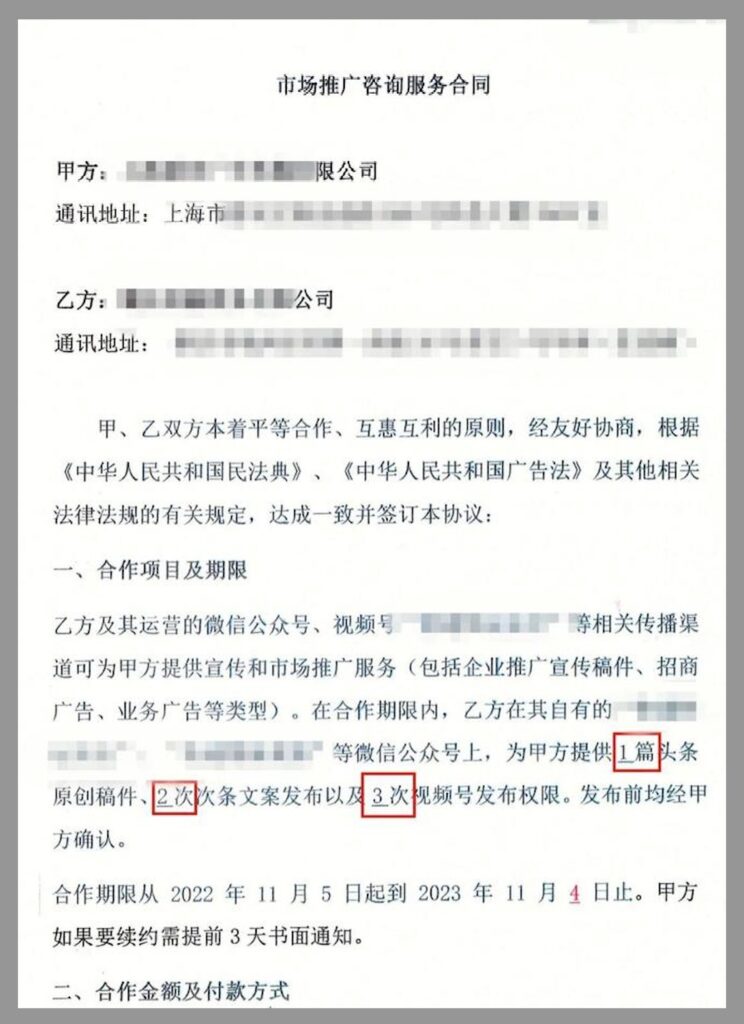

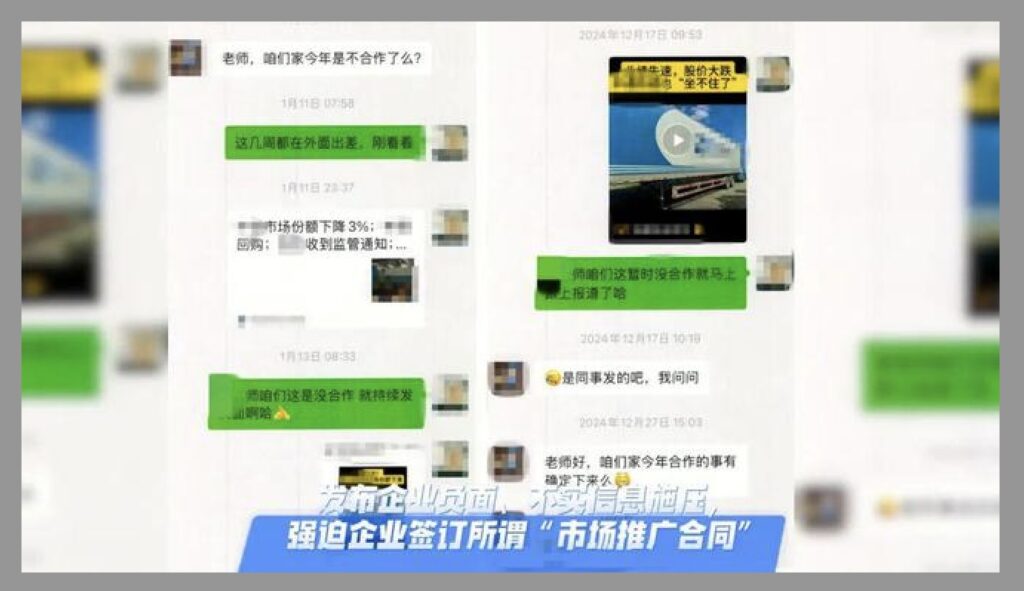

As described by police, the alleged extortion scheme followed a clear pattern. Ding would first publish damaging content about a company. He would then approach the company offering to sign what he called a “market promotion contract,” which essentially came with a promise to cease coverage. These contracts generally were for between 20,000 and 100,000 yuan annually, or about 2,750 to 14,000 dollars. The fee structure was calibrated, said police, based on a company’s size and “tolerance capacity” (承受能力) — essentially referring to what Ding deemed companies would be able to pay.

Ding’s operation reportedly netted multiple companies, with one executive telling police he was forced to pay over 100,000 yuan annually to stop the attacks, only to face renewed pressure after the expiration of “market promotion” contracts.

This latest case in Shanghai reflects the broader phenomenon of news extortion that has plagued China’s commercialized media landscape since at least the mid-1990s. Despite periodic crackdowns and isolated cases like this one, the practice persists — in large part because it exploits fundamental vulnerabilities in China’s heavily controlled information ecosystem. In this environment, media can have extraordinary power through perceived connections to the state press system, turning this authority to profit, while the media control policies of the Chinese Communist Party normalize the practice of removing “negative” or “sensitive” reporting. At the same time, there are no independent professional associations to advance ethical conduct within the media.

The investigation in Shanghai continues, police say, and Ding likely faces criminal charges for extortion.