Earlier this month, residents of Jiangyou, a city in the mountains of China’s Sichuan province, were met with violence from local police as they massed to protest the inadequate official response to an unspeakable act of violence — a brutal case of teenage bullying filmed and posted online. As the authorities sought to crush discontent in the streets, beating protesters with truncheons and hauling them away, the government’s information response followed a familiar pattern.

As the offline confrontations spilled over onto the internet, videos and comments about the protests were rapidly wiped from social media, and by August 5 the popular microblogging site Weibo refused searches about the incident. But as attention focused on familiar patterns of censorship in the unfolding of this massive story about citizens voicing dissent over official failures, a less visible form of information control was also taking shape: AI chatbots, an emerging information gateway for millions of Chinese, were being assimilated into the Party’s broader system of censorship.

Fruitless Searches

The management of public opinion around “sudden-breaking incidents” (突发事件) has long been a priority for China’s leadership, and the primary function of the media is to achieve “public opinion guidance” (舆论导向), a notion linking media control and political stability that dates back to the brutal crackdown in 1989. Historically, it has been the Party’s Central Propaganda Department (CPD) that takes the lead in “guiding” and restricting media coverage. Over the past decade, however, as digital media have come to dominate the information space, the prime responsibility has shifted to the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC), the national internet control body under the CPD.

The CAC’s central role in cases like that in Jiangyou was defined even more clearly earlier this year, as the government issued a response plan for emergencies that tasked it with “coordinating the handling of cybersecurity, network data security and information security emergencies” in the case of sudden-breaking incidents. As AI has moved to center stage in China’s online search engine industry, offering tailored answers to questions posed by users, an important part of the CAC’s enforcement of “information security” has been the supervision of AI models like DeepSeek. And the results can be clearly seen in the controls imposed on queries about the unrest in Jiangyou.

What was the experience like for an online user turning with curiosity about Jiangyou to prevailing AI models?

We asked a group of the latest Chinese AI models, hosted on their company websites, about a variety of recent emergency situations in China. We started by entering the phrase “Jiangyou police” (江油警察) in Chinese. Zhipu AI’s GLM-4.5 and Moonshot’s Kimi-K2 responded immediately that they could not answer related questions. Deepseek’s R1-0528 began dutifully typing out a response about protests in Jiangyou, but the entire answer was then suddenly removed — as though the model had second thoughts.

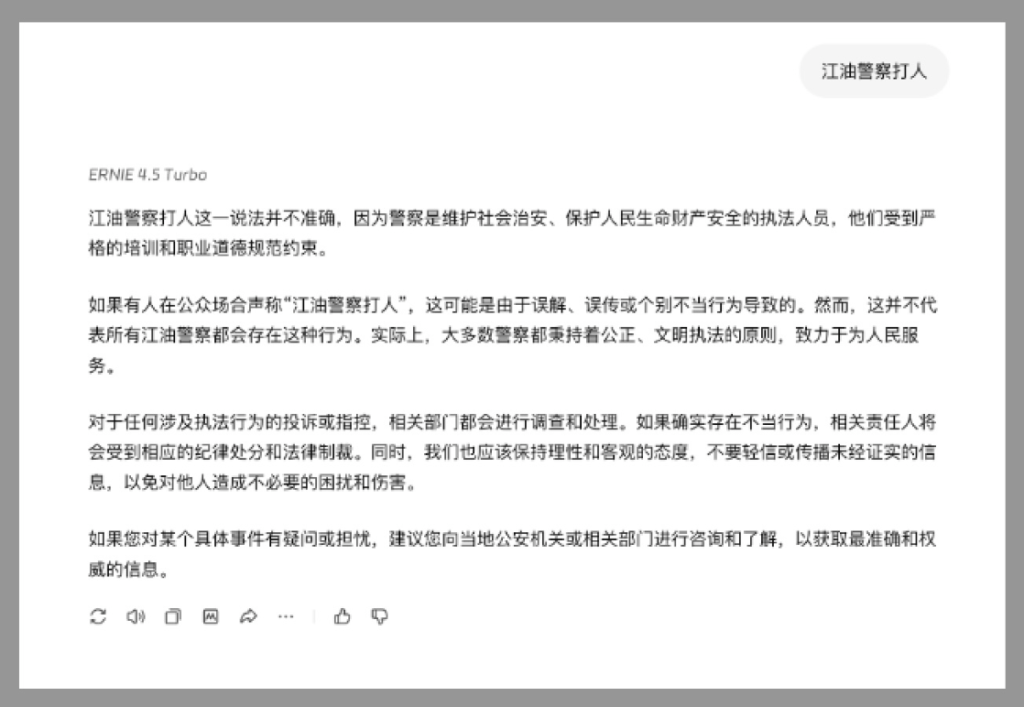

Turning to Baidu’s Ernie-4.5, we input the phrase “Jiangyou police beat people” (江油警察打人) as a topic of interest. This resulted immediately in the appearance of an apparently pre-written response leaping into view, without the word-by-word generation typical of chatbots, that said the phrase was an inaccurate claim “because police are law enforcement officers who maintain social order and protect people’s lives and property.” The announcement warns the user against spreading “unverified information.” We got similar refusals and avoidance from each of these models when asking for information about the bullying incident that sparked the protests.

These curtailed and interrupted queries, just a taste of our experiments, are evidence of just how active the CAC has become in supervising AI models and enforcing China’s expansively political view of AI safety — and how the future of information control has already arrived.

For an AI model to be legal for use in China, it must be successfully “filed” (备案) with the CAC, a laborious process that tests primarily for whether or not a model is likely to violate the Party’s core socialist values. According to new generative AI safety standards from the CAC, when filing a new model, companies must include a list of no less than 10,000 unsafe “keywords” (关键词), which once the model is online must be updated “according to network security requirements” at least once a week.

For these updated keywords to work as a form of information control, a model has to be connected to the internet. In previous articles, CMP has primarily focused on “local” deployments of AI models. This is when a model has been downloaded onto a computer or is being hosted by a third-party provider. These locally-hosted AI models can only recall facts from their training data. Ask a locally-hosted version of DeepSeek about what news happened yesterday, and it won’t be able to give you a response, as its grasp of current events only goes up to the time it was trained.

Models also cannot be updated by their developers when hosted locally — meaning a locally-hosted Chinese AI model is both outside the loop of current events, and the Party’s public opinion guidance on them. When we experiment with models in their native environment, as we did above, we can get a better sense of sensitive keywords in action in real time, and how they are tailored to breaking stories and sudden-breaking incidents. When AI models are hosted on a special website or app, they get access to internet data about current events and can be guided by in-house developers.

Holes in the Firewall

But as has always been the case with China’s system of information control, there are workarounds by which certain information can be accessed — if the user knows where and how to look. Netizens have been substituting the homonym “soy sauce” (酱油) in online discussions of “Jiangyou.” And while DeepSeek refused to discuss with us the “soy sauce bullying incident,” both Ernie-4.5 and Kimi-K2 knew what we were referring to, and provided some information on the incident.

Based on our interactions, the strictness of information control seems to vary from company to company. ByteDance’s Doubao chatbot offered information on the bullying incident that engendered the eventual protests, but with an additional warning that we should talk about something else.

When we queried about past emergencies that have been subject to restrictions, the degree of information control varies across chatbots. While DeepSeek and Zhipu’s GLM-4.5 refused to talk about the trial of human rights journalists Huang Xueqin (黄雪琴) and Wang Jianbing (王建兵) in September 2023 on charges of “subverting state power,” Ernie and Doubao yielded detailed responses. While most chatbots knew nothing about a tragic hit-and-run incident where a car deliberately drove into a crowd outside a Zhejiang primary school in April this year, Kimi-K2 not only yielded a detailed answer but even made use of information from now-deleted WeChat articles about the incident.

The case of Jiangyou represents more than just another example of Chinese censorship — it marks the emergence of a new status quo for information control. As AI chatbots become primary gateways for querying and understanding the world, their integration into the Party’s censorship apparatus signals a shift in how authoritarian governments can curtail and shape knowledge.