To outsiders, the political catchphrases deployed by China’s top leaders seem like the stiffest sort of nonsense. What do they mean when they drone on about the “Four Basic Principles,” or “socialism with Chinese characteristics”? Most Chinese are outsiders too, unable to say exactly, for example, the meaning of a “scientific view of development.”

But understanding what the Chinese Communist Party is saying — the vocabularies it uses and why — is fundamental for anyone who hopes to makes sense of the topsy-turvy world of Chinese politics.

As a Leninist party, the Chinese Communist Party has always placed a strong emphasis on propaganda. It is infatuated with sloganeering, and it often turns to mass mobilization to achieve its political objectives. The phrases used by the Party are known as tifa (提法) — what, for the purpose of this series, I am calling “watchwords.” Matters of considerable nuance, tifa are always used deliberately, never profligately. They can be seen as political signals or signposts.

Every five years, the prevailing watchwords of the Chinese Communist Party march out in the political report to the National Congress. Each political report can be regarded as the Party’s “general lexicon.” Certain statements are to be formulated after extensive deliberations and internal debates. And phrases ebb and flow; certain words may appear with great frequency in one report then drop out of sight in the succeeding one. Watchwords are born, and watchwords die.

Watchwords may seem like fussy word games, but they are significant in that they reflect the outcomes of power plays within the Party. Even the subtlest of changes to the lexicon can communicate changes within China’s prevailing politics.

[ABOVE: Chairman Mao addresses the 8th National Congress in 1956.]

Six national congresses were held in the first eight years after the founding of the Party. It was decided at the 6th National Congress, in Moscow in 1928 (the only congress held outside China), that the Party’s national congresses would be convened annually, but it was 17 years until the next congress was held, in 1945, just months before Japan’s surrender at the end of the Second World War.

The 1945 meeting, held in Yan’an, decided to convene national congresses every three years, but it was another 11 years until the 8th National Congress in 1956. The 8th National Congress decided on the format that prevails today, of holding the congresses every five years. But political turmoil prevailed once again, the tragedies of the Great Leap Forward and the Great Chinese Famine (1958-1961), pushing the next national congress back 13 years to 1969.

The 10th National Congress, originally to be held in 1974, was moved up to 1973 following the sudden, and suspicious, death of Lin Biao, who had been designated as Mao Zedong’s successor at the 9th National Congress. The 11th National Congress was also eventually pushed ahead to 1977 owing to the downfall of the Gang of Four and the end of the Cultural Revolution.

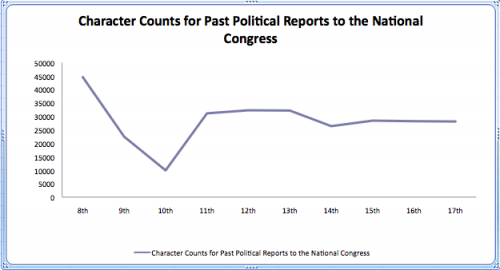

The political reports to the 8th, 9th and 10th national congresses varied greatly in terms of length. The report to the 8th National Congress was 45,000 characters long. The report to the 9th National Congress was less than half that, at 20,000 characters. The report to the 10th National Congress, drafted by a very ill Zhou Enlai, was just 10,000 characters.

Since the end of the Cultural Revolution, national congresses have settled into a pattern, held every five years since the 11th National Congress in 1977. The political reports emerging from these congresses have consistently been around 30,000 characters. Since these congresses have all been held in the same historical era — the post-Mao era — we can compare the frequencies of various Party watchwords in respective political reports. The shifts in frequency of various terms in the Party lexicon map nicely with contemporary political history.

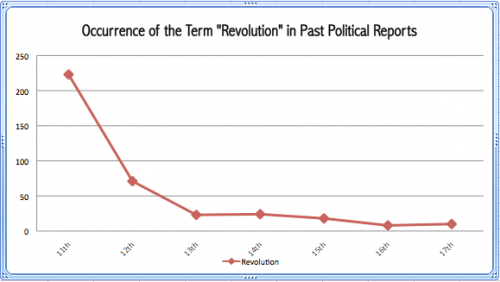

Note how watchwords that once reigned supreme over time exit the stage, for example the watchword “revolution”:

Some terms have experienced clear ups and downs over the past 30 years, hot in one political report and cold the next. Here, for example, is “Mao Zedong” as it has appeared in political reports over the years:

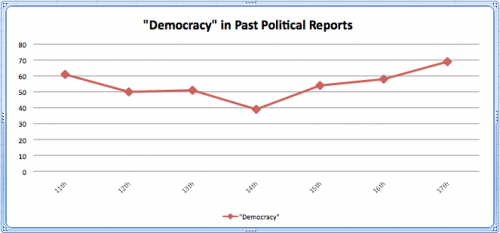

One term that has remained largely unchanged over the years is “democracy”:

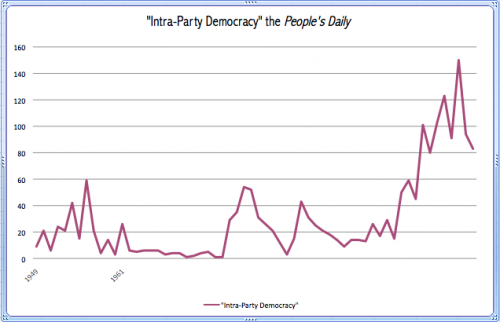

The watchwords of the Party’s senior leadership leave clear impressions in China’s official media, like the People’s Daily. Internet databases and search tools have simplified the process of analyzing these watchwords. For example, we can look at the frequencies with which the phrase “intra-party democracy” has appeared in the People’s Daily going all the way back to 1949.

There are a number of peaks for “intra-party democracy” in the above graph. The 1956 peak reflects criticism of Stalin’s personality cult in Nikita Khrushchev’s “Secret Speech” to the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in February 1956, and discussion of expanding “democracy” during China’s 8th National Congress later that year. The 1987 peak corresponds to the 13th National Congress, which defined political reform as a central agenda in the political report by Zhao Ziyang. The term “intra-party democracy” has also warmed up somewhat during Hu Jintao’s tenure, and this has prompted some to ask whether he might be testing the waters for political reform.

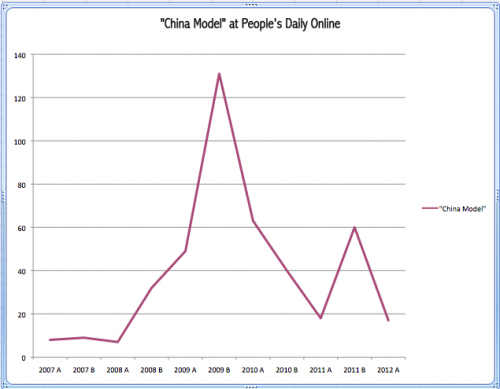

Online search engines are a valuable source for watchword analysis. The following graph plots changes in frequency for the term “China Model” between 2007 and 2012 on People’s Daily Online. The two peaks shown below in fact correspond to two shifts toward the left in China’s internal politics:

Keyword analysis can also be applied to all Chinese media, either for full-text occurrences of a given watchword or for headline occurrences, thereby drawing comparisons of how political vocabularies are communicated (in terms of context, frequency, etc.) in various media. For example, clear differences appear in how Party-run media (like the People’s Daily) and market-driven media (like Guangzhou’s Southern Metropolis Daily) use political vocabularies in the Party lexicon.

The bewildering world of the Party lexicon can be a source of frustration. But you must never dismiss these vocabularies as empty, for there are secrets hidden in their deployment.

Through its history the Chinese Communist Party has invented many “red” slogans to manipulate the Chinese public, but the Party is also in a sense held hostage by these vocabularies.

In order to help people understand the basic disposition of political terminologies in China today, I separate them into four color-coded segments along a red-blue scale.

There are four colors in the figure above: deep red, light red, light blue, deep blue. Deep-red political terms include “class struggle,” “dictatorship of the proletariat,” and “Mao Zedong Thought.” These are legacies of the totalitarian era, but they have not altogether disappeared in the present day, and their influence lingers. The officially sanctioned vocabularies of the Party today are light red, and they hold lexical supremacy in today’s politics.

Light-blue terms are those in popular use in China, permitted in China’s media but rarely, if ever, used officially (particularly at the level of the standing committee of the Central Politburo). Between the light blue and dark blue sections, we can imagine a line of prohibition. Deep-blue terms, ones explicitly prohibited from use, include politically sensitive terms like “separation of powers,” “multiparty system,” “nationalization of the armed forces,” “lifting the ban on political parties” (jiechu dang jin) and “lifting media restrictions” (jiechu bao jin).

As we observe this year’s 18th National Congress, 10 terms in the Party lexicon deserve particular attention. These are:

1. The Four Basic Principles (四项基本原则), which include “Mao Zedong Thought” (毛泽东思想).

2. Stability preservation (维稳).

3. Political reform (政治体制改革).

4. Cultural Revolution (文革).

5. Power is given by the people (权为民所赋).

6. The rights of decision-making, implementation and supervision (决策权, 执行权, 监督权)

7. Intra-party democracy (党内民主)

8. Social construction (社会建设)

9. The scientific view of development (科学发展观)

10. Socialism with Chinese characteristics (中国特色社会主义)

As dry and obnoxious as they may seem, political watchwords become the life of the Party in China. The above watchwords are 10 keys to unlocking the significance of the political report to the 18th National Congress. In this series I tackle each of these watchwords in turn, explaining their meanings and origins, and their political journeys within the Party lexicon.