China Newspeak

Aristocratic Character?

In recent days in China a buzz of speculation has surrounded an article published on January 10 by the Study Times, a publication of the Central Party School, the training academy for Party leaders. At issue is the suggestion in the article that Xi Jinping, the General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party, has “an aristocratic character” (贵族气质). Such language apparently shocked many readers, judging from comments on social media.

Called “Comrade [Xi] Jinping Stresses that We Must Be People Who Flow With the New Era” (近平同志强调要敢做时代的弄潮人), the article in question was an interview with Lin Bin (林彬), the former deputy head of the government office in the city of Fuzhou, corresponding to Xi Jinping’s time in the leadership there in the early 1990s. Lin is currently the CEO of The Straits Publishing and Distribution Group, a state-run company.

In the interview, Lin relates a story of how several friends, knowing he had served with Xi Jinping in Fujian province, had asked for his impressions of the leader.

I said: “Do you want the long version, or the short version?”

My friends asked: “What’s the short version?”

I said: “The short version is that I can sum up my impression of him in eight words — the feelings of the people, an aristocratic character. I’ll just say that, and you can glean what you will.”

Why would this word, “aristocratic,” cause such a buzz of speculation?

First of all, we have to understand that within the political culture of the Chinese Communist Party, language is not at all flippant or incidental. There is no such thing (not if one is disciplined) as off the cuff, though leaders with sufficient strength might have greater latitude in toying with language – like Mao Zedong and his poetic reference to flatulence. While the Party’s discourse may be fluid to a certain extent, there is an unmistakable orthodoxy, reflected clearly in the Party media and in official documents. Second, we need to understand that the word “aristocrat,” which suggests distance and differentiation from the people, is not a word of praise within CCP discourse.

And so people had to ask: Wasn’t it an act of scarcely veiled criticism for a high-level official to praise Xi Jinping as having an “aristocratic character”?

In Chinese, this question surrounded what we refer to as “high-level black” (高级黑), this being a political term meaning to satirize in a guarded or euphemistic manner, sometimes through overwrought praise. A close cousin of this act of poor discourse discipline is “low-level red” (低级红) – referring essentially to acts of sycophantic ingratiation (to borrow from John King Fairbank and Merle Goldman) that are so overwrought as to become humorous or invite disdain, undermining the Party’s credibility.

When Chinese in the context of the CCP’s political culture talk about “aristocrats,” this means something very different from the word in a Western context. It is political terminology that is tantamount in most cases to an accusation of “confusion” (混乱), or fundamental problems in attitude or conduct.

Over a century ago, in 1919, 26 year-old Mao Zedong wrote a short essay of around 2,000 characters called “The Great Union of the Masses” (民众的大联合) in which the word “aristocrat” appeared 14 times. “Since ancient times,” he wrote, “there have been various forms of union including the union of those in power, the union of the aristocracy, and the union of capitalists.”

The People’s Daily wrote back in 1966 that: “Chairman Mao published many splendid revolutionary essays in the Jianghu Commentary magazine that he launched and edited in Changsha, and he raised many slogans of struggle and full-fledged revolution about striking down the old world, and making the aristocracy and the capitalists quake before the people.”

If we search back over the 74-year history of the People’s Daily, we can see many different types of “aristocrat”: the “decadent aristocrat” (没落贵族); the “feudal aristocrat” (封建贵族); the “aristocratic landlord class” (地主贵族阶级); the “capitalist aristocrat” (贵族资本家); the “children of aristocracy” (贵族子弟); the “elite aristocrat” (精神贵族); the “imperial aristocracy” (皇室贵族); the “aristocratic class” (贵族阶层); the “aristocratic serf masters” (贵族农奴主); “aristocratization” (贵族化); “aristocratic dictatorship” (贵族专政); the “aristocratic caste system” (贵族等级制度); the “aristocratic hereditary system” (贵族世袭制), and so on.

The bottom line is that none of these are appellations any leader would wish for within the mainstream political discourse of the Chinese Communist Party.

Let’s consider just a couple of examples that were used quite frequently in the history of the CCP. One of the most prominent is “aristocratic grandfather” (贵族老爷), a term that was equivalent in the eyes of the Party to “the exploitative classes” (剥削阶级).

One story in the People’s Daily dating back to October 1979, right as the cusp of the reform era, tells how the military commander Peng Dehuai, known for his spartan style of living, once learned of several villas in a scenic area outside the capital that had been given over to the use of certain senior officials, but sat empty most of the year. After he learned of this, Peng went off in the middle of the night to keep watch over the villas. His personal secretary urged him to get some sleep, but Peng refused. “He ignored him and said to himself, ‘There are those who would have us become aristocratic grandfathers, like ministers serving the monarch. I’m afraid people don’t realize that these are temples built for the new imperial ministers of today!”

Another common term was “aristocratic classes” (贵族阶层). At the Second Plenum of the Eighth Party Congress in 1956, Liu Shaoqi warned: “Given the situation in several socialist countries, it seems national leaders could become a special class, a new aristocratic class.” At the same Party meeting, Mao Zedong said: “We must be alert against fostering a new bureaucracy, a new noble class separated from the people.”

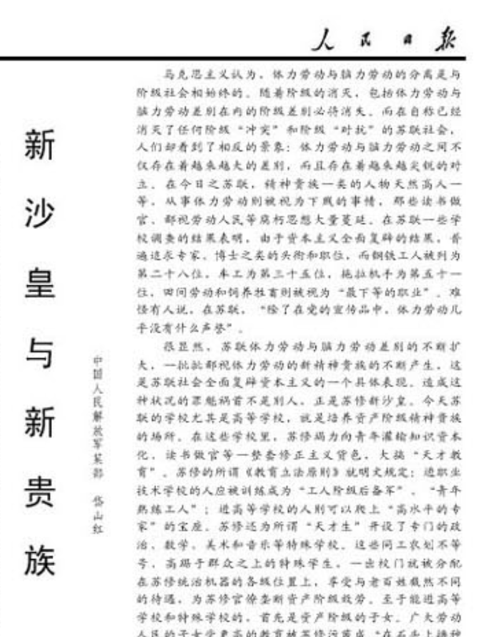

Within the mainstream political discourse, the term “new aristocracy” is often used to refer to the emergence of a new elite class within the CCP owing to problems of corruption, which you can see in the headline of the following People’s Daily article.

The references above should suffice to show that the “aristocrat” is not a term of praise within the dominant political discourse in China, but rather is quite categorically a word with negative associations. But now, puzzlingly, we have this word being applied to Xi Jinping.

In February 2019, the Central Committee of the CCP issued a “New Opinion on the Strengthening of the Party’s Political Building” (关于加强党的政治建设的意见), which made a point as it elucidated the so-called “Two Protections” (两个维护) – protecting General Secretary Xi Jinping as the “core,” and protecting the unified central authority of the CCP Central Committee – of clarifying several instances of “incorrect language” (错误言行). The document emphasized that, “[Party members] must not engage in any form of ‘low-level red’ or ‘high-level black,’ and absolutely must not act in a two-faced manner toward the Central Committee, engage in double-dealing, or engage in ‘pseudo-loyalty.’”

For leaders inclined to comment on Xi Jinping’s “aristocratic character,” this might be a time for reflection.