Image by Kevin Dooley, available at Flickr.com under CC license.

Xi Jinping’s political report, delivered at the opening of the 20th National Congress of the CCP last Sunday, is a monster of a text to grapple with. You might think of it as an edifice of little snap-together blocks, all specialized terms and slogans molded within a century-long history of CCP political discourse, much of it drawing also on Marxist, Leninist, and Stalinist prose.

Many, if not most, of these specialized formulations, or tifa (提法), come loaded with meanings and associations that demand historical as well as contextual readings to really understand what they are meant to signal. For example, to truly understand the notion of “common prosperity” (共同富裕), a phrase that Xi Jinping has made a centerpiece of his contemporary vision of promoting greater economic fairness and balanced development, you have to grapple with the term’s unique history under Mao Zedong as well as Deng Xiaoping, which CMP wrote about in-depth in 2021.

In a very real sense, the political report is the reconstruction every five years of a complex structure and tradition of political rhetoric to broadly define priorities within the CCP, condense power relations, and build the present as a historical moment that necessitates and legitimizes Party rule.

And this brings us to the first misunderstanding that has proliferated in the wake of Xi’s report.

This was a political report, not a “work report”

A number of news stories and summaries in recent days have referred to Xi Jinping’s report on October 16 as a “work report.” In fact, this is inaccurate in two ways.

First, as the brief summary above suggests, the political report is more fully about CCP politics and the political ideas that animate it. By contrast, work reports serve more as reviews of tasks set and accomplished. They are, in other words, more about execution than vision. This is why the annual report delivered to the National People’s Congress (NPC) by China’s premier is indeed referred to as a “work report,” or gongzuo baogao (工作报告). It is why the report delivered by Xi Jinping just eight days ago, at the 7th Plenum of the 19th CCP Central Committee, was also referred to as a “work report.”

Second, “work report” is not generally used in Chinese, at least correctly, to refer to these important once-every-five-years events. Instead, the reports delivered at CCP national congresses are referred to in long-hand form as simply “reports” with reference to the respective congress: Report to the 20th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (中国共产党第二十次全国代表大会上的报告).

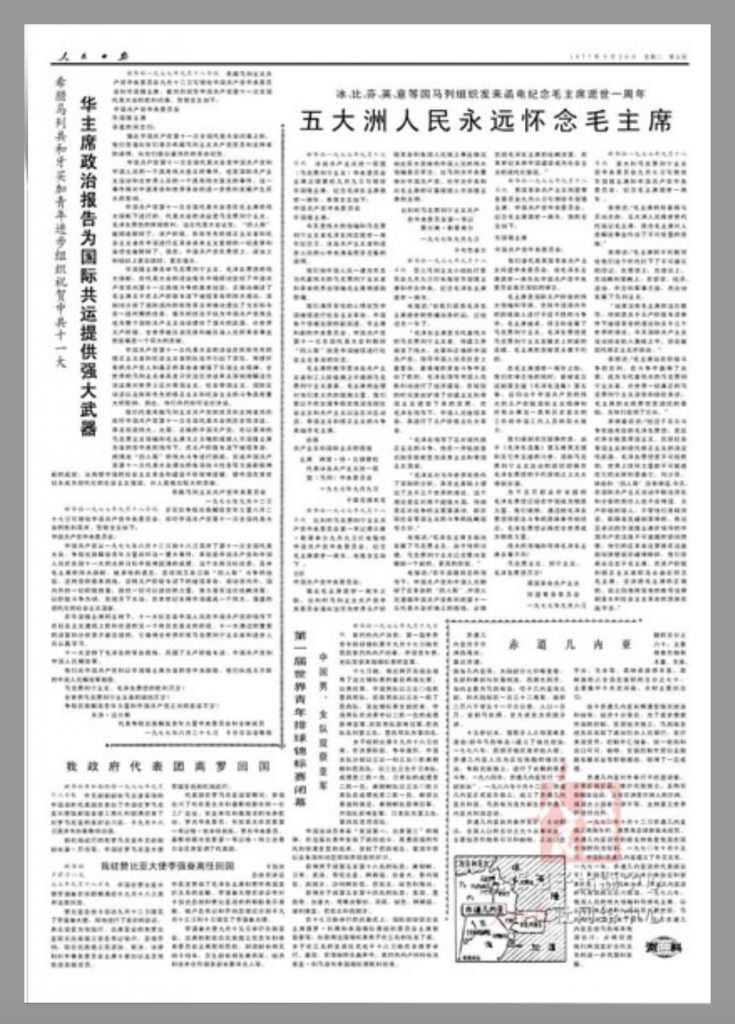

In short-hand form, they are more properly called “political reports,” or zhengzhi baogao (政治报告) — and so they have been called for decades. The image below is a page from the People’s Daily in September 1977, following Hua Guofeng’s political report to the 11th National Congress in August of that year. The headline reads: “Chairman Hua’s Political Report Provides a Powerful Weapon for the International Communist Movement.”

The term “political report” is commonly used, including in external communication. Wrote one commentator on Toutiao over the weekend, anticipating Xi’s report: “The Party’s leadership is the greatest political advantage of China’s diplomacy, and the political reports of the Party’s congresses on foreign affairs have made clear China’s judgment and view of the world situation.”

The distinction is an important one. While work reports do of course also include political signaling and can be heavy on CCP jargon, they are more directed in their response to specific policies and objectives, and are more oriented to current challenges.

The reading of Xi’s report to the 20th National Congress as a “work report” might lead us to suspect that it would address major political and security events directly, even perhaps in the manner of a State of the Union — which leads us to the second misunderstanding in evidence this week.

Current events may be in the background, but they are not the point

As the initial quick reads poured in on Sunday and Monday following Xi’s address, there was much chatter about what Xi Jinping emphasized, and what he left out. As the BBC’s correspondent in Beijing summed up on Twitter:

Notable for what wasn’t in Xi’s speech: no mention of soaring youth unemployment; no mention of the property crisis; no mention of economic & social pain from Zero-#Covid in #China. Overall, it was 2 hours heavy on standard rhetoric and light on specific solutions to problems.

These absences were notable, indeed. Not, mind you, as reflections of what things might have been expected but were not addressed, but as reflections of how political reports are meant to be. Political reports are always heavy on “standard rhetoric,” those tifa snap-together blocks. They do not offer specific solutions to problems, even if they may point broadly in the direction of solutions (remember “common prosperity”?).

And political reports most certainly do not mention points of sensitivity such as soaring youth employment. This occasion, like all public and formal events hosted by the CCP, is about keeping the cards close, not laying them on the table. It is a carefully scripted drama through which the power of the Party, its leader, and its ideas are meant to be elevated and amplified.

Perhaps with the “work report” frame in mind, some observers anticipated mention by Xi Jinping of the war in Ukraine — and its absence, with not even an oblique mention, was regarded as newsworthy. “Xi made no mention of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which Beijing refuses to criticize,” reported the Associated Press.

It is a carefully scripted drama through which the power of the Party, its leader, and its ideas are meant to be elevated and amplified.

But in fact, mention of any current or recent war whatsoever would have been a history-making precedent for CCP political reports. Remember, this is not about current events, even if they shape the tone of certain sections of the speech, or linger in the margins; the references, for example, to “not fearing ghosts” (不怕鬼) and “not fearing pressure” (不怕压), were likely flares in Xi’s most recent report to signal tensions with the United States and the West.

Looking back on full-text political reports stretching back to 1997, I could find not a single reference to any current or recent war in the six political reports delivered during this period. The references to war are invariably ideological concepts, such as a “people’s war” (on corruption), general notions (“information war”), or historical wars that lend an epic nature to the Party’s overarching vision of itself. Just half of the reports I reviewed referred to specific wars at all, and these were the “Chinese people’s war of resistance against Japan,” the “world war against fascism,” and the “war of liberation.”

Concrete References to war in CCP National Congress Reports:

1997 = Opium War, War of Resistance Against Japan, War of Liberation

2002 = None

2007 = None

2012 = None

2017 = Opium War

2022 = War of Resistance Against Japan, World War Against Fascism

The absence of Ukraine resonates with those of us experiencing this political event from the outside. How can such a flagrant violation of a country’s sovereignty as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine not be acknowledged in such an important political address?

But this was entirely expected. And expectation is the perfect segway to a third misunderstanding of Xi Jinping’s political report that merits a mention.

No, this report was not substantially shorter

Hot takes served during the first 24 hours and more following Xi Jinping’s address noted a seemingly quite significant fact — that the report was apparently far shorter than reports in previous years. Coming in at just around two hours as delivered from the podium in the Great Hall of the People, the speech was roughly one-third shorter than Xi Jinping’s report five years earlier.

What could it mean?

One explanation early on was that this could be explained through the lens of factional politics, and there were just fewer factions now given Xi Jinping’s overwhelming dominance (for more, see CMP’s analysis of “Major Points” ahead of the Congress). As one researcher wrote at Chatham House: “The 20th Party Congress report is significantly shorter than the 19th, which is a clear indication of Xi’s success in centralizing power.”

In fact, official commentary on state-run television in China immediately after the broadcast of the political report noted clearly that what Xi had intoned from the floor was not the full report, but rather “picking out the key points,” or tiao zhongdian (挑重点).

The full-text report, which circulated through various online channels in the hours immediately after Xi’s performance, was 31,600 characters in length, just over 800 characters short of his 2017 report to the 19th National Congress. Both versions can be downloaded here at the China Media Project in searchable Word format.

Another important characteristic of CCP political reports is that they are quite consistent in length. Political reports in the pre-reform period may show greater variance, but here is a list of the character lengths for reports going back to 1997:

1997 = 28,400

2002 = 28,180

2007 = 28,000

2012 = 29,101

2017 = 32,450

2022 = 31,600

As you can see, the reports are remarkably similar in length — making comparisons convenient for researchers. But the similarity is not so remarkable when you consider again that these reports emerge through a rigid and carefully controlled process of discourse construction (and likely, yes, some degree of factional deliberation), in which there is no room for the incidental or spontaneous. Even the sustained applause in sections of the report is a carefully crafted performance.

Reading Xi Jinping’s political report is a painstaking process. Like any puzzle, it is sometimes best to begin with the corners and edges and work your way in. On that note, please look forward to our modest observations on language now missing in the 2022 report.