THE CMP DICTIONARY

Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence

Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence

As Americans went to the polls in November 2024, a spokesperson for the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs fielded a question about how the presidential election would affect relations with the US. Regardless of who won, he said, China would continue to conduct its diplomacy according to “the principles of mutual respect, peaceful coexistence, and win-win cooperation.”

That assurance, soon repeated in Xi Jinping’s message of congratulations to President-elect Donald Trump, had echoes of an early mainstay of PRC foreign policy, dating back to the 1950s. The “Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence” (和平共处五项原则) were a vague set of sentiments devised to serve as the ideological bedrock for the Non-Aligned Movement — nationals worldwide that chose not to take a side in the Cold War rivalry between the US and the Soviet Union. Their legacy has persisted to the present day, with Xi Jinping calling them the “cornerstone” of the country’s foreign policy. The principles, which emerged from talks between PRC Premier Zhou Enlai and Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru in 1954, are as follows:

- Mutual respect for territorial integrity and sovereignty (互相尊重领土主权)

- Mutual non-aggression (互不侵犯)

- Mutual non-interference in each other’s internal affairs (互不干涉内政)

- Equality and cooperation for mutual benefit (平等互惠)

- Peaceful Coexistence (和平共处)

The story is well-known in India, where the Principles are viewed as a cooperative effort between Zhou and Nehru. An Indian interpreter at those talks, however, wrote in the Hindustan Times in 2004 that the credit should go to Zhou alone, whom he said had brought the complete list to the talks over the two countries’ shared border in Tibet that began in December 1953.

Five Principles for the Third World

Outcast by developed Western countries that continued to recognize Chiang Kai-shek’s Republic of China and on the verge of a dramatic split with the Soviet bloc, Mao Zedong looked to the Global South — what he termed the “Third World” — for allies and acolytes. As early as Mao’s declaration of the People’s Republic on October 1, 1949, he began to articulate an early version of the Five Principles, saying that his government would engage with any country agreeing to “the principles of equality, mutual benefit, and mutual respect for territorial sovereignty.” China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs cites this and similar wording in the “Common Program” of the PRC’s first legislative session as proof Mao and his circle had already created the “major content” of the Principles by the time they appeared at the 1953 talks with India.

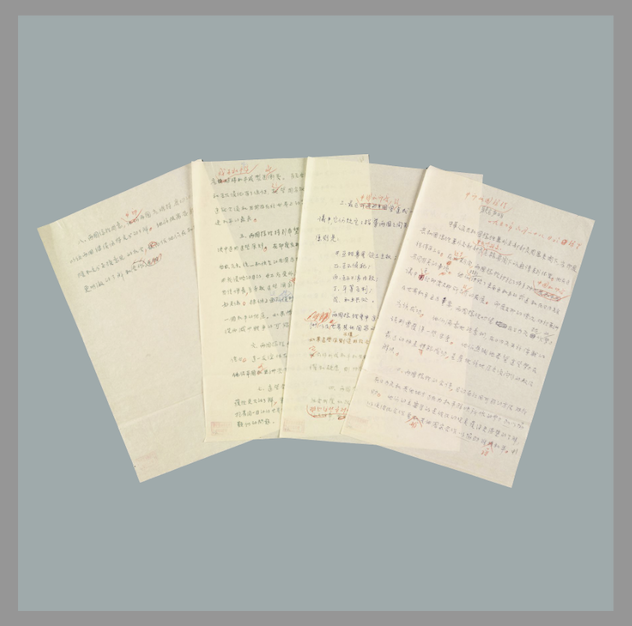

The Principles have endured to this day, albeit with two small but crucial tweaks. After engaging in similar talks with the Burmese government later in 1954, all three countries agreed to change the fourth point from “mutual gain” (互利) to “mutual benefit” (互惠). The second change came in 1955, when the first point was altered by Zhou Enlai and his ministers from “mutual respect for territorial sovereignty” to “mutual respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity” 互相尊重主权和领土完整.” This was because, according to a foreign ministry think tank, the original rendering “might be interpreted as meaning the territory that is now under the actual control of the Chinese government” — precluding, for example, Taiwan, as well as Hong Kong and Macau at that time.

1955 also saw the Principles go global thanks to the Bandung Conference, when representatives from newly independent Asian and African countries gathered in Indonesia to promote cooperation and enhance their presence in international affairs. Zhou Enlai was there, giving a cordial face to Mao’s ambitions to lead this movement and promoting the Five Principles as the basis for how the PRC would deal with other nations in a postcolonial world. When the final Bandung Declaration included the Five Principles, plus five more gleaned from the United Nations Charter, both China and India claimed credit for this accomplishment.

In the decades since then, the Five Principles have served China well. They burnished the country’s reputation as a leader of the “Third World,” the apex of a third pole in international affairs beyond Washington and Moscow. And for their service, the Principles have also been enshrined and accorded an ever-growing list of decorations by the Party-state. Deng Xiaoping codified the Principles into China’s constitution in 1978. When the Principles turned 30 in 1984, then-Premier Zhao Ziyang reaffirmed that they were created to “break the old international order” of geopolitical hegemony. When China faced diplomatic isolation after the Tiananmen Massacre, Li Peng cited the Five Principles in an overture to US President Richard Nixon.

Superpowers for World Peace

To this day, China continues to appeal to the sanctity of “territorial integrity and sovereignty” and “non-interference in internal affairs” to bring nations of the Global South on board in its ongoing efforts to erase Taiwan from the global stage and lay the groundwork for a PRC takeover. To this day, the language of the third principle of non-interference in internal affairs is reliably invoked whenever China faces international criticism about its human rights record.

On the 60th anniversary of the Principles in 2014, Xi Jinping said the principles had been “jointly advocated” by India, China, and Myanmar, each making their own “important contributions.” But in his 70th-anniversary speech ten years later — just as relations with New Delhi frayed over, again, their shared border in Tibet — Xi said they were the brainchild of Chinese leaders alone, who then magnanimously included the other countries in their joint statement. He concluded the talk by giving the Principles the ultimate, if backhanded, compliment: hailing them as a “starting point” that eventually led to his Xi Jinping Thought on Diplomacy (习近平外交思想).

As the US and China edge closer to what Chinese state media frequently characterize as a “new Cold War,” Xi believes that, from the 1950s to the present day, “China has given the answer” for world peace. That answer has not changed greatly over the years, but the world they exist in has. As the PRC emerges as a superpower, its talk of “mutual benefit” can mean schemes in which it wields disproportionate power over smaller partners; insistence upon “non-interference” can become carte-blanche to ignore international standards and obligations; and devotion to “territorial integrity” can take the form of expansionist claims on lands and peoples beyond their grasp. For a superpower, demanding peace can mean pacification.

Alex Colville

The CMP Dictionary

C

D

F

G

M

N

P

S

- Scaling the Wall

- Science

- Second-Generation Reds

- Security

- Seeking Progress in Stability

- Seeking Truth From Facts

- Self-Revolution

- Seven Bottom Lines

- Six Adheres

- Smart Governance

- Sneaky Visit

- So-Called

- Socialite

- Soft Resistance

- Soul and Root

- Soundless Saturation / Quietly Nourishing

- Sovereignty

- Speaking Politics

- Streamlining Services

- Strong Cyber Power