On May 19, China’s top law enforcement agency released measures for the roll-out of “cyber IDs” (网络身份认证), a new form of user identification to monitor internet users. Although the measures were released as a draft over the summer last year, they have only just been finalized, and will come into effect in mid-July.

According to the measures, introduced by the Ministry of Public Security (MPS), each internet user in China will be issued with a unique “web number,” or wanghao (网号), that is linked to their personal information. While these IDs are, according to the MPS notice, to be issued on a strictly voluntary basis through public service platforms, the government appears to have been working on this system for quite some time — and state media are strongly promoting it as a means of guaranteeing personal “information security” (信息安全). With big plans afoot for how these IDs will be deployed, one obvious question is whether these measures will remain voluntary.

Whose Online is it Anyway?

The measures bring China one step closer to centralized control over how Chinese citizens access the internet. The Cybersecurity Law of 2017 merely stipulated that when registering an account on, say, social media, netizens must register their “personal information” (个人信息), also called “identifying information” (身份信息). That led to uneven interpretations by private companies of what information was required. Whereas some sites merely ask for your name and phone number, others also ask for your ID number — while still others, like Huawei’s cloud software, want your facial biometrics on top of it.

The plan for a centralized app has been quietly coming into focus over the past 10 years. For example, even before the Cybersecurity Law came into effect, the MPS was filing patents in 2015 and 2016 to work out how to create an ID for netizens beyond just their IP addresses. A pilot version of the MPS app was quietly uploaded to Apple’s app store as far back as June 2023.

This app is being sold to Chinese citizens as an extra layer of protection for personal data online. The state-run Xinhua News Agency reported on May 23 that the app would cut down the amount of spam netizens received when registering their personal details online. On May 25, China Central Television (CCTV), the country’s state broadcaster, said cyber IDs would lower the risk of personal information being leaked by private internet platforms.

That last promise could prove a crowd-pleaser. There have been several seismic cases of internet users’ private information being leaked from Chinese internet platforms. In 2020, hackers extracted the private details of more than 500 million people through the social media platform Weibo. As late as March this year, the daughter of a Baidu executive caused a public storm by posting the private details of netizens she was bickering with — seeming to suggest that she had obtained the details through the company’s databases.

A Timeline of China’s Cyber ID

How the country’s system for digital identity verification came to be—

and where it is going.

Early Patent Development

Cybersecurity Law Implementation

Pilot App Uploaded

Official Service Launch

Public Comment Period

Final Measures Published

Implementation Takes Effect

Offline Expansion Plans

A subsequent exposé by China Economic Weekly (中国经济周刊) showed how easy it is for anyone online to collect the personal information of others — sometimes known as “box opening” (开盒), or doxxing — via a smooth operation on the messaging app Telegram, where hackers collate all sorts of personal information and sell them for a profit. As Telegram lies outside the country’s technical system of internet controls known as the Great Firewall, it has the added advantage of being beyond Chinese regulation.

The measures formalize what has quietly been taking shape for years. The MPS has already launched the Cyber ID app, which has been downloaded 16 million times, with 6 million users applying for digital credentials, according to government figures.

The system works by establishing the MPS as a central intermediary between users and online platforms. Citizens upload their personal information to the government app in exchange for a “web number” (网号) or “web certificate” (网证) — essentially a string of digits that serves as their digital identity. When accessing participating platforms, users present this government-issued credential rather than their raw personal data. The arrangement means private internet companies no longer directly collect users’ personal information, instead relying on government verification to grant access.

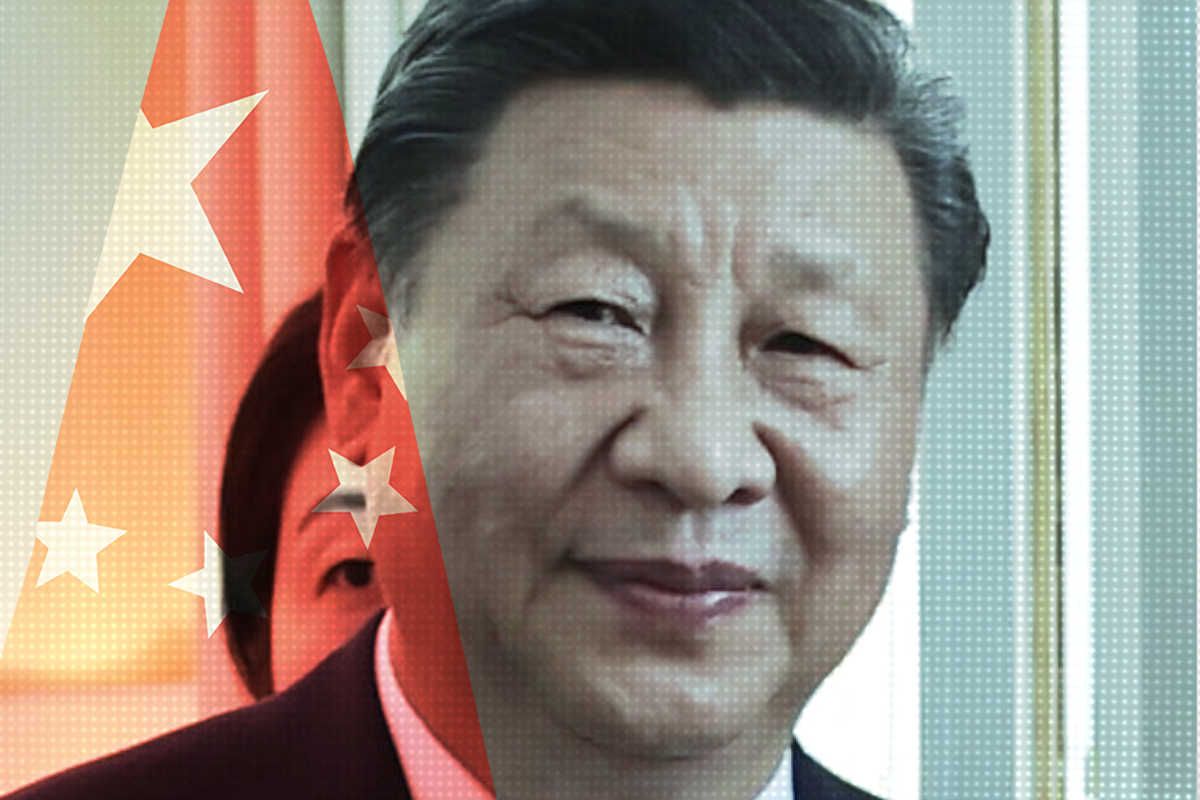

State media coverage suggests the voluntary nature of these IDs may be temporary. CCTV recently aired detailed step-by-step instructions for viewers to apply — the voluntary nature of the system mentioned just once in passing at the beginning of the segment. The tone throughout implied that enrollment was expected, not optional.

Xinhua sought to address privacy concerns, promising that “security is the top priority” for the new MPS platform. In a telling final line, however, as the news agency relayed assurances from the MPS that the new system “will not affect people’s normal use of internet services,” betraying broader public anxieties about an emerging national ID system. The need for such assurance hints at what officials have not said — that those opting out of the cyber ID system could eventually find themselves locked out of digital life entirely.

When the draft measures first came out last year, they sparked heated debate on Chinese social media. In a now-deleted post, Lao Dongyan (劳东燕), an outspoken law professor at Tsinghua University, questioned the government’s commitment to personal information protection by pointing out that the country’s billion plus internet users had already been obligated to surrender their personal information to hundreds of sites and apps as a condition of use. There is little hope of protecting this information, she said, if the bulk of it has already been relinquished to private interests.

Can the MPS platform really be expected to be safer than the hundreds of private platforms to which users have hitherto been obliged to surrender their data? Before you answer that, bear in mind that Shanghai’s National Police Database was hacked in 2022.

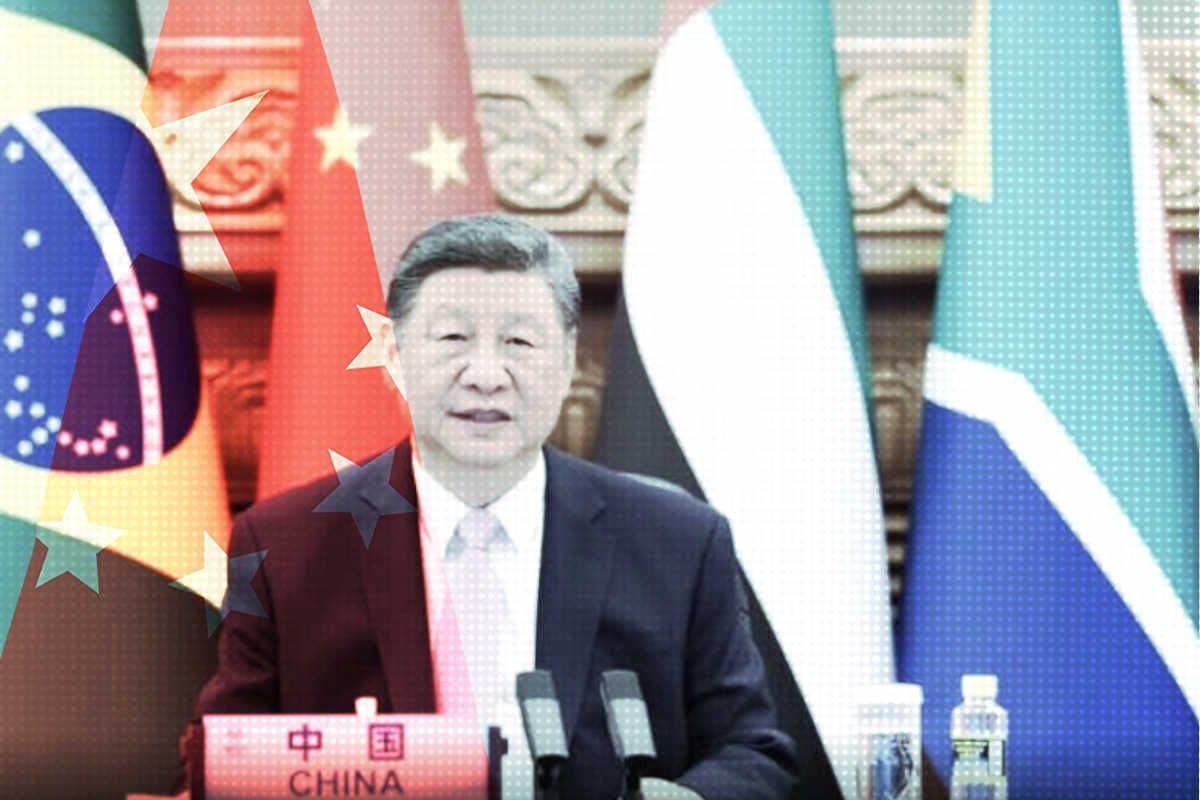

Beyond the key question of personal data security, there is the risk that the cyber ID system could work as an internet kill switch on each and every citizen. It might grant the central government the power to bar citizens from accessing the internet, simply by blocking their cyber ID. “The real purpose is to control people’s behavior on the Internet,” Lao Dongyan cautioned last year.

Writing on WeChat last year, a law professor at Peking University said the cyber ID system would encourage self-censorship, even if it could offer an additional layer of personal data protection.

Take a closer look at state media coverage of the evolving cyber ID system and the expansion of its application seems a foregone conclusion — even extending to the offline world. Coverage by CCTV reported last month that it would make ID verification easier in many contexts. “In the future, it can be used in all the places where you need to show your ID card,” a professor at Tsinghua’s AI Institute said of the cyber ID. Imagine using your cyber ID in the future to board the train or access the expressway.

This long-term planning suggests the government is gently corralling the public into accepting a controversial policy. While Chinese state media emphasize the increased ease and security cyber IDs will bring, the underlying reality is more troubling. Chinese citizens may soon find themselves dependent on government-issued digital credentials for even the most basic freedoms — online and off.