This week we begin our short list of top media stories with an interesting controversy that brewed online over suggestions from college entrance examination authorities in the municipality of Chongqing that students sitting for next year’s examinations would need to pass a “political investigation,” or zhengshen (政审), process in addition to the normal testing procedures. The term zhengshen dates back to the political turmoil of China in the 1950s through the 1970s, when the Chinese Communist Party dug into the family backgrounds and connections of Chinese to determine their political suitability.

After using the term zhengshen in a Q&A post on its official WeChat account, igniting the controversy, examination authorities in Chongqing tried to back peddle, claiming that media had misrepresented the story. The official Chongqing Daily newspaper, however, also used the term liberally in its coverage of changes to testing procedures for next year.

Also on the list this week — the 5th World Internet Conference (WIC) was held in the historic Zhejiang water town of Wuzhen, but with lukewarm attendance from foreign representatives, and more subdued showings by Chinese tech figures; and news of the suicide death of Hu Xin, a key figure for many years behind official Party commentaries in the People’s Daily, drew interest from social media users.

___________________

THIS WEEK IN CHINA’S MEDIA

November 3-9, 2018

➢ As storm brews over supposed “political investigation” portion of college entrance exams in Chongqing, authorities blame journalists

➢ Chemical leak in Fujian province prompts anger as local government downplays impact

➢ World Internet Conference gets lukewarm participation and coverage

➢ Journalist Hu Xin, a key writer behind official People’s Daily commentary bylines, commits suicide

[1] As storm brews over supposed “political investigation” portion of college entrance exams in Chongqing, authorities blame journalists

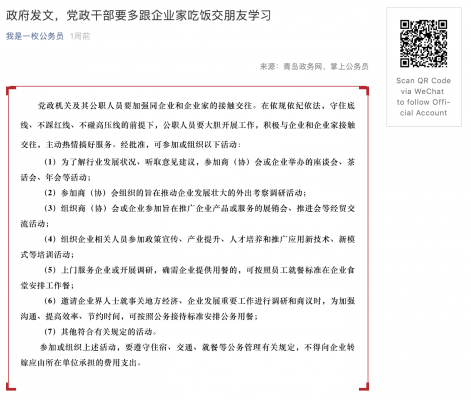

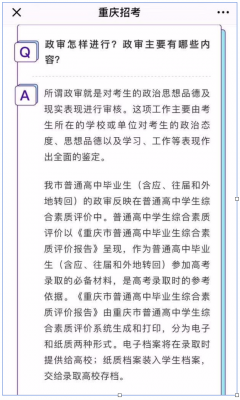

On November 2, a post made to the official WeChat account of the Chongqing Education Examination Board (教育考试院), “Chongqing Entrance Exam” (重庆招考), caused anger and consternation online. The post, called “The Hot Questions for Testing Students Are All Right Here” (考生关注的热点问题, 都在这儿), said students taking the 2019 college entrance examination would be subjected to a “political investigation,” or

zhengshen (政审), in addition to the normal testing requirements. The post prompted fierce criticism as it invoked for many the politically motivated interrogations into family backgrounds that were common in the 1960s and 1970s, in the era before economic reform and opening.

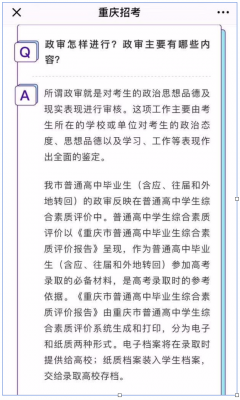

In the image to the left, a question in the original Chongqing Education Examination Board post asks: “How will political investigation be carried out? What will the chief content of political investigation be?” The term clearly used here is

zhengshen (政审), invoking the political campaigns of the 1960s-1970s.

On November 6, the official

Chongqing Daily, the mouthpiece of the city’s top Party leadership, said that the “political investigation” procedure in question would entail an inquiry into the “political ideas and character” (政治思想品德) of testing students. The results given following the “political investigation” process, said the paper, would be either “qualified” or “disqualified.” Those who failed to earn a “qualified” grade in the political investigation process would not be allowed to sit for the regular examination, according to the newspaper report. The work of conducting the political investigations would be entrusted to the schools or work units of the testing students.

As discussion simmered online following the post, the WeChat public account “China Newsweekly” (中国新闻周刊) quoted Luo Shenqi (罗胜奇), the director of the Chongqing Education Examination Board as saying that, “Concerning political examination, this is just misreporting by journalists and the media. We call [the two examination portions] political and ideological examination (思想政治的考核) and pragmatic performance examination (现实表现的审核). Journalists misunderstood this as a process of ‘political examination’ (政审).”

On November 8, the Chongqing Education Examination Board again explained: “Referring to the political and ideological examination of students as a process of ‘political investigation’ was non-standard usage and inaccurate. On the afternoon of November 8, an employee at our office also responded incorrectly when speaking to a reporter. The content and methods [of examination] for the general 2019 university examinations in Chongqing in terms of ‘examination of the political and ideological character’ of exam takers are unchanged.”

The term “political examination” is an abbreviated form of

zhengzhi shencha, a process of organised examination of the political attitudes, family background, past conduct and social connections of individuals employed from the 1950s through the 1970s.

Key Sources:

Chongqing Daily (重庆日报):

重庆2019年普通高考11月7日开始报名

WeChat public account “China Newsweekly” (中国新闻周刊):

重庆教育考试院独家回应:高考“政审”系误读,不是查你祖宗八代

Chongqing Educational Examination Board (重庆市教育考试院):

重庆市教育考试院关于普通高校招生“思想政治品德考核”有关信息的说明

WeChat public account “Zhang Ming 0011” (张鸣0011):

不该有的倒退

Global Times (环球时报):

单仁平:从“政审”一词引发议论和担心谈起

[2] Chemical leak in Fujian province prompts anger as local government downplays impact

Early in the morning on November 4, as a chemical called C9 was being transferred between a transport ship operated by Donggang Petrochemical Industry Co. Ltd. (东港石油化工实业有限公司) and a dock in the coastal city of Quanzhou in Fujian province, a broken connecting tube resulted in the leaking of 6.7 tonnes of the substance, according to local authorities. By November 5, the day after the incident, the head of the Agriculture, Forestry and Water Bureau in the Quanzhou Port announced that the “chemical pollutants had already been entirely cleared away.” However, posts made to social media by residents in the area told a markedly different story. On November 8, authorities in Quanzhou made a preliminary determination that the production accident had resulted in the contamination of a .6 square kilometre area of the port, and that approximately 300

mu, or 200,000 square meters, of agricultural land had been affected. As of November 9, 52 local residents had been treated.

The impact of the chemical industry has been a longstanding issue in the Quanzhou area in recent years. Xiaocuo Village (肖厝村), the area where the recent leak occurred, has typically been referred to as “the leading aquaculture village” (养鱼第一村). But over the years a number of chemical processing factories have been built in the area, and there are constant questions over whether these factories are in violation of environmental and safety regulations.

Key Sources:

Beijing Youth Daily (北京青年网):

泉州一石油化工船舶泄露6.97吨碳九 环保局:海域清理已基本完成,将检测水质及海产品

Xinhua Daily Telegraph (新华每日电讯):

碳九对人体危害几何?为何清理工作还未结束?何时才能解决厂居混杂问题? 三问福建泉港碳九泄漏事故

[3] World Internet Conference gets lukewarm participation and coverage

On November 7, the curtain opened on the 5th World Internet Conference (WIC) in the town of Wuzhen in China’s coastal Zhejiang province. The opening ceremony was attended by Huang Kunming (黄坤明), director of the Central Propaganda Department, who presented a welcome letter from President Xi Jinping and delivered a keynote speech.

Lacklustre participation by prominent tech figures, both Chinese and non-Chinese, was a focus of discussion on social media. Some noted that Jack Ma, the Alibaba founder who announced his retirement this year but has remained publicly visible, made no public address whatsoever at this year’s conference. Moreover, just one representative from a Silicon Valley company was listed as a speaker at the conference.

This year’s WIC opened against the backdrop of frustration, both domestic and international. Domestically, internet censorship has arguably never been stricter in China. Internationally, the sense among Silicon Valley companies is that the China market is hopelessly inaccessible.

China’s first World Internet Conference was held in 2014, hosted by the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC). WIC was a key early initiative of then cyber czar Lu Wei, head of the CAC, who last month plead guilty in court to accepting 32 million yuan in bribes. Lu is currently awaiting sentencing.

Key Sources:

Xinhua News Agency (新华社):

第五届世界互联网大会开幕 黄坤明宣读习近平主席贺信并发表主旨演讲

The Paper (澎湃新闻网):

世界互联网大会这五年:一场盛会改变乌镇,乌镇带动一座城

Bloomberg (彭博社):

China’s Grand Internet Vision Is Starting to Ring Hollow

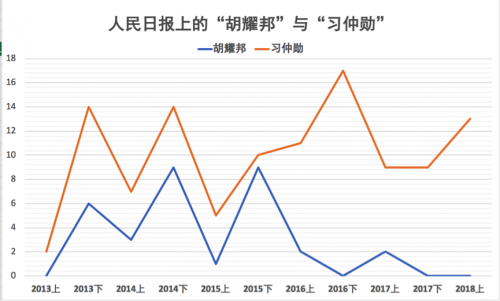

[4] Journalist Hu Xin, a key writer behind official People’s Daily commentary bylines, commits suicide

WeMedia accounts (自媒体) reported on November 6 that Hu Xin (胡欣), the former editor-in-chief of the

People’s Daily‘s News Frontline journal — an official publication dealing with media and communication — had committed suicide by leaping from the 19th floor of the newspaper’s office building. Sources close to the journalist said he had long suffered from depression. He was 66 years old.

Hu Xin is not a media figure immediately recognisable to many in China, but behind the scenes he was an important figure helping to shape high-level commentaries from the

People’s Daily. He was a core member of the writing team behind the official bylines “Ren Lixuan” (任理轩) and “Ren Zhongping” (任仲平), which were often used in the official newspaper to convey important statements from the Party’s central leadership.

Hu started his career in 1990 in the theory department at the People’s Daily, and from 1998 to 2004 he served as a toop editor of the section.

Key Sources:

WeChat public account “Mei Tong She” (媒通社):

著名媒体人、《新闻战线》原总编胡欣女士坠楼离世!