Children in a commune nursery school in China in 1959. Image from the Chinese book “10th Anniversary Photo Collection of the People’s Republic of China 1949-1959” published by 10th Anniversary Photo Collection of the People’s Republic of China Editorial Committee, available at Wikimedia Commons under CC license.

The phrase “common prosperity” was given prominence in the media coverage that attended the August 17, 2021 meeting of the Central Committee for Financial and Economic Affairs ( 中央财经委员会). Both the headline of the official Xinhua release coming out of the meeting and the lower-third text during the evening broadcast of CCTV’s Xinwen Lianbo (新闻联播) included the newly significant words, imbedded in the longer phrase “promoting common prosperity in high-level development” (在高质量发展中促进共同富裕).

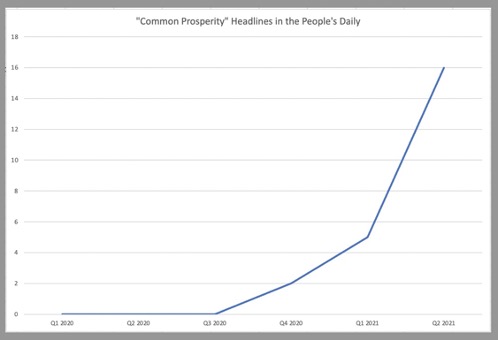

As Bloomberg noted in an August 2021 report on “common prosperity,” however, Xi Jinping’s use of the phrase had already soared that year, well before the August meeting, reflecting his stated commitment to address income disparity in China, which came with efforts to restrain “unreasonable income” and to encourage the super-rich to give back to society. The graph below shows the number of articles in the newspaper since January 2020 that use the term “common prosperity” in the headline.

But the phrase “common prosperity” is much older than the wave of attention in 2021 seemed to indicate.

Where does the phrase “common prosperity” originate within the history of CCP discourse, and what can this history tell us about the present struggle to define the direction of China’s development?

Collective Resources for Common Prosperity

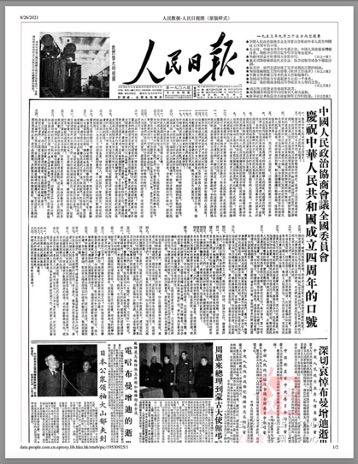

The phrase “common prosperity” first appeared in the People’s Daily on September 25, 1953, as the paper published a list of 65 approved slogans for the commemoration of the fourth anniversary of the founding of the PRC. Slogan number 38 was less a slogan, in fact, than a lengthy spill of exclamations:

Male and female peasants! [We must] work to increase production and save! [We must] work for the fall harvest, reducing losses and doing everything possible to enlarge the harvest! [We must] work at autumn planting, preparing for winter-time production, striving for a rich harvest next year! [We must] work on water conservation, on plowing and sowing deeply, on improving seeds, increasing fertilizer accumulation, and reasonable fertilizer application to increase yield per unit area! . . . . Men and women of the agricultural production mutual support teams! Men and women of the agricultural production cooperatives!

United together, [we must] bring into play the spirit of collectivism, improving productivity, increasing production of grain and other crops, increasing income, striving for lives of common prosperity, according to the principles of willingness and mutual benefit . . . .

The first article using “common prosperity” in a headline in the People’s Daily was published on December 12, 1953, part of a series in the paper called “Promoting the General Line to the Peasants” (向农民宣传总路线). The choice before the people was simple, it argued. There were just two possible paths forward. One was capitalism, described as “a road of a few getting rich, while the vast majority are poor and destitute” (资本主义的路是少数人发财、绝大多数贫穷破产的路). The other was of course socialism.

The article, “The Path of Socialism is the Path to Common Prosperity” (社会主义的路是农民共同富裕的路), made clear that “common prosperity” could only happen through collective ownership, meaning that the resources of production – including land, large farm equipment, major livestock and so on – were held in common. By the end of 1952, land reforms in the young People’s Republic of China had nearly been completed, and preparations were being made in the leadership for the nation’s first Five-Year Plan, modeled on the planned economy of the Soviet Union under Stalin.

While the main focus on the First Five-Year Plan was to be on industrialization, the CCP also sought to transform the agricultural sector. Collectivization was the order of the future, beginning with the reorganizing of Chinese society into mutual help teams. “When the means of production are publicly owned, there will be no more exploitation of people by people,” said the People’s Daily article. Common prosperity, therefore, meant that resources were held in common.

Therefore, the development of mutual aid teams and cooperatives can not only avoid division among the peasants and avoid the path of capitalism, but can also enable peasants to achieve common prosperity step by step and finally reach a socialist society.

On December 16, 1953, four days after the above-mentioned article, the CCP released its “Resolution on the Development of Agricultural Production Cooperatives” (关于发展农业生产合作社的决议), which is often cited as the origin of the term “common prosperity” in its earliest, Maoist, understanding.

Overcoming Egalitarianism

The 1950s dismissal of capitalism as “a road of a few getting rich” when it came to the question of “common prosperity” was turned on its head in the late 1970s, as Deng Xiaoping came to power and pursued a new economic development strategy, “reform and opening,” or gaige kaifang (改革开放). The changes that came in the wake of the Third Plenary Session of the 11th Central Committee in December 1978 brought about a radical rethinking of the notion of “common prosperity” that in fact encouraged “a road of a few getting rich” as a means of enriching all.

The theoretical basis of Deng Xiaoping’s approach to regional economic development was that “common prosperity” could be reached by allowing certain regions and groups of people to get rich first. This idea was summed up best in the phrase “permitting a few peasants to get rich first” (允许一部分农民先富起来), which allowed more industrious and better-connected households to accrue wealth rapidly. Various permutations of this phrase can be found in the official press from around 1979, referring first to “peasants” (农民) and to “commune members” (社员). The phrase became popularized internationally in reference to “people” only after Deng told visiting New Zealand Prime Minister David Lange in March 1986: “Our policy is to let some people and some regions get rich first, in order to drive and help the backward regions, and it is an obligation for the advanced regions to help the backward regions.”

The link between “get rich first” and “common prosperity” was there from the very beginning of the debate over the substance of reform and opening in the late 1970s.

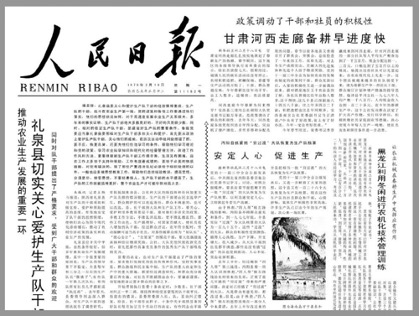

The first mention of the “get rich first” concept in the People’s Daily came on February 19, 1979, in an article to the right of the masthead that reported the remarks of the top leader in Gansu province, following the “good policies” of the central leadership. The leader was reported as having told a group of commune members shortly after the Spring Festival that certain highly productive members “can get rich first, taking first steps forward in agricultural modernization” (可以先富起来,在农业现代化上先走一步).

The change in policy was reportedly welcomed by some. “This idea was accepted by more and more teams and became the guiding idea for some team cadres and masses as they made plans and introduced measures to increase productivity in the spring production,” the article said.

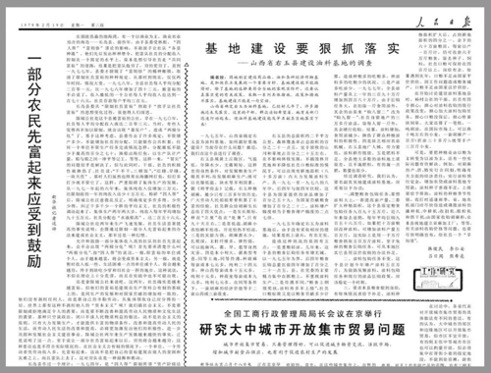

But the more controversial aspects were plainly visible in a second article appearing on page two of the same edition of the paper. The article, bearing the headline, “A Portion of Peasants Getting Rich First Should Be Encouraged” (一部分农民先富起来应受到鼓励), sought to argue through the restrictions that had been placed on production in the name of socialism, and to dispel fears that changes in the system of wealth distribution meant a return to capitalism.

After a political potshot against Lin Biao (林彪) and the then much-derided “Gang of Four” (四人帮), the article rejected outright the previous notion of “common prosperity” as spelled out and practiced in the Mao era. “What was originally intended to guide commune members down a road to ‘common prosperity,’ in the end made a rich team poor, and then poorer and poorer,” it said.

Far from marking a return to capitalism, empowering the individual forces of production could lead, the article said, to greater wealth for all. The alternative was an empty political devotion to principles of collectivism that dragged everyone down (to paraphrase).

We engage in socialism, not to limit or refuse to meet the needs of individuals, but to constantly improve and enhance the needs of the material and cultural life of the working people. That practice of talking only emptily about politics and shutting up about the material interests of the people is in no way a principle of socialism.

The article suggested that one of the chief problems limiting progress toward prosperity was the failure to recognize that there were in fact gaps in income distribution among peasants in the socialist era. The “Gang of Four” had “used restrictions to keep rich teams down, so that they could not step forward,” thereby depriving socialism of its vitality. Restrictions had been carried out in the name of egalitarianism (平均主义), which was now, clearly, to be a dirty word:

First of all, [we must] acknowledge [income] gaps, oppose egalitarianism, and allow and encourage the allocation of more to members of advanced teams with higher collective income, allowing them to live better, and to take the lead for poorer teams, serving as models and allowing poorer teams to be encouraged and see hope.

Once the “Gang of Four” had been smashed, said the article, communes had begun to “correct the egalitarianism of equality between those who work more and those who work less” (纠正干多干少一个样的平均主义).

Such opposition to egalitarianism, while upholding the wealth-generating vitality of the individual, was part and parcel of the effort in the early reform period to reframe Chinese socialism and set the country on a new path of development that could lead to a “common prosperity” re-defined. All of these concepts could be seen readily in an article appearing on April 15, 1979, in the People’s Daily, bearing the headline: “A Few Getting Rich First and Common Prosperity” (一部分先富裕和共同富裕). The article laid out the CCP’s new approach to “common prosperity” in clear terms:

Our Party’s leading of the peasants along the path of socialism is about ‘making all rural people achieve common prosperity.’ Allowing some peasants to get rich first is a practical policy to achieve common prosperity.

我们党领导农民走社会主义道路,就是‘要使全体农村人民共同富裕起来’。允许一部分农民先富起来,正是为了达到共同富裕的一项切合实际的政策。

The previous notion of “common prosperity,” panned as a legacy of the period when “Lin Biao and the ‘Gang of Four’ ran amok,” was a stultifying egalitarianism. “[If] we practice egalitarianism, artificially limiting wealth in order to safeguard the poor, taking from the wealthy to make amends for the poor, ‘eating from a big pot of rice,’” the article said, “then the hope of reaching common prosperity under socialism can only be a flower in the mirror, or a pie in a picture.”

A People’s Daily article in December 1979 (共同富裕不是平均富裕) was even more explicit in its drawing of lines: “Socialism is not egalitarianism, and common prosperity does not mean equal wealth,” it said.

Re-redefining “Common Prosperity”

Understand the above history, and Deng-era criticisms of “pie in a picture” notions of egalitarianism, and you can begin to understand the anxieties arising in China today around the re-surfacing of the notion of “common prosperity” over the past year. Deng Xiaoping enabled and empowered new forces of practicality and productivity that led China into an era of unprecedented growth, creating substantial wealth through much of Chinese society.

So Xi’s recent emphasis on wealth redistribution, and his re-opening of the question – visible throughout the Party-state media – of how to promote “common prosperity,” naturally begs the question of whether, and to what extent, he plans to unravel the support for private enterprise that has marked the reform era. Is he a “pie in a picture” idealist, determined, as some investors fear, to drag a vibrant private sector into an ideological campaign for social values over commercial ones? Is he promoting a new egalitarianism?

“Chinese experts have increasingly expounded upon the idea of common prosperity in the media, while Chinese firms scramble to join in the ideological edification,” analyst Sara Hsu wrote recently in The Diplomat. “Whether China’s flourishing private sector can continue to grow under such a heavy hand has yet to be seen.”

Nikkei Asia wrote on August 18, 2021, in an article headlined, “Xi Moving Away From ‘Get Rich First,’” that “President Xi Jinping has called for stronger ‘regulation of high incomes’ in the latest sign that a 10-month campaign targeting China’s largest technology companies is rapidly expanding to encompass broader social goals.”

It was concerns like the above, responding to the historical baggage of “common prosperity,” that prompted Han Wenxiu (韩文秀), executive deputy director of the General Office of the Central Financial and Economic Affairs Commission, to speak to the issue at a briefing in Beijing in late August 2021 held by the Central Propaganda Department to promote a published volume called The Historical Mission, Action and Values of the Chinese Communist Party (中国共产党的历史使命与行动价值). At the briefing, Han sought to allay fears that efforts to tackle inequality might stifle the economy and discourage entrepreneurialism and investment.

“Common prosperity means doing a proper job both of expanding the pie and dividing the pie, on the foundation of the comprehensive building of a moderately prosperous society, energetically promoting high-quality development,” Han said. Invoking Deng’s language about letting a few “get rich first,” he emphasized:

[We] must encourage hard work to get rich, entrepreneurship and innovation to get rich, and permit some people to get rich first, and after getting rich helping others to grow richer. [We] will not ‘kill the rich to help the poor.’

要鼓励勤劳致富、创业创新致富,允许一部分人先富起来,先富带后富、帮后富,不搞 ‘杀富济贫.’

Echoing the language from the late 1970s that rejected egalitarianism as a value inhibiting development, Han described Xi’s concept of “common prosperity” as “not a pure and simple egalitarianism, but a common prosperity in which there is still some disparity.” This in turn was echoed by Xinhua News Agency in an English-language release yesterday in which it stressed that “common prosperity is not egalitarianism.”

Casting about for a scapegoat for what was clearly also a serious internal messaging problem, coming in conjunction with its recent string of sweeping purges of large private enterprises in China, the Xinhua release pointed a finger at reports outside of China, stressing that common prosperity was “by no means robbing the rich to help the poor as misinterpreted by some Western media.”

But what “common prosperity” really means for Xi Jinping and the current leadership of the CCP is a question that will have to remain open for now. There can be little doubt that the changes suggested by the leadership would require, at the very least, as Professor Pan Helin (盘和林), argued in China Youth Daily, require “a change in people’s ideas of self-interest.” And in the absence of a vibrant civic space, such changes to the ideas that underpin society are a difficult, and potentially intrusive, proposition. As with the development of this phrase in the past, the meaning of “common prosperity” will become clearer in future rhetoric as well as in future practice.

David Bandurski

The CMP Dictionary

C

D

F

G

M

N

P

S

- Scaling the Wall

- Science

- Second-Generation Reds

- Security

- Seeking Progress in Stability

- Seeking Truth From Facts

- Self-Revolution

- Seven Bottom Lines

- Six Adheres

- Smart Governance

- Sneaky Visit

- So-Called

- Socialite

- Soft Resistance

- Soul and Root

- Soundless Saturation / Quietly Nourishing

- Sovereignty

- Speaking Politics

- Streamlining Services

- Strong Cyber Power