THE CMP DICTIONARY

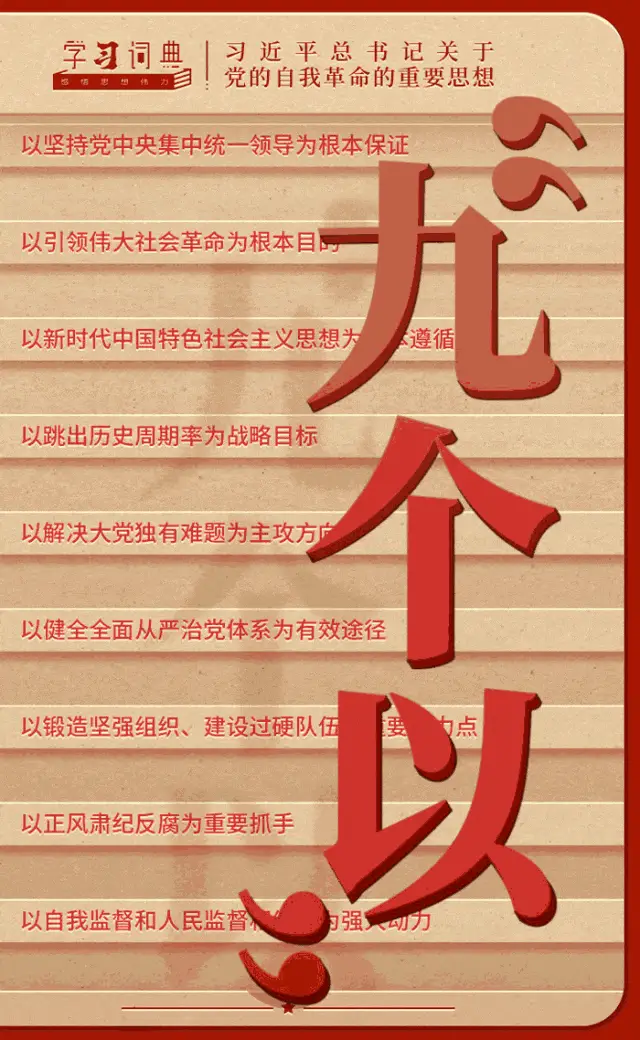

Nine Withs (Nine Requirements)

Nine Withs (Nine Requirements)

In early January 2024, the Chinese Communist Party held the Third Plenary Session of the 20th Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI), a regular conference of the CCP’s highest anti-corruption body that was meant to serve as a progress report on the Party’s efforts to root out malfeasance and point the way to future action.

In his speech (重要讲话) to the meeting, Xi Jinping announced that after a decade of concerted anti-corruption efforts, “the fight against corruption has won an overwhelming victory and has been comprehensively consolidated” (反腐败鬥争取得压倒性胜利并全面巩固). This was a claim, in no uncertain terms, to Xi’s unmitigated success as General Secretary in tackling the problem of corruption within the CCP over the first decade of his leadership.

Job done, Xi Jinping seemed to say.

Immediately after, however, Xi seemed to signal the opposite. “[The] situation,” he said, “remains grim and complicated” (形势依然严峻複杂). Equally unambiguous, this language contradicted the “overwhelming victory” he had claimed just moments earlier.

How can these contradictory statements be reconciled? How can Xi be saying in one breath that an “overwhelming victory” had been achieved, and in the next admit that things are dire and far from complete — and that it is essential, therefore, for the CCP to “resolutely win the protracted battle of the anti-corruption struggle” (坚决打赢反腐败鬥争攻坚战持久战)?

“[The] fight against corruption has won an overwhelming victory and has been comprehensively consolidated” . . . . BUT . . . “the situation remains grim and complicated.”

The answer, simply put, is that the protracted battle against corruption is not at all about corruption, but rather about the defense and consolidation of Xi’s power. And this secret is embedded in one of the key phrases to emerge from Xi’s speech and from the Third Plenary Session of the 20th CCDI — the confusingly named “Nine Withs” (九个以), which might also be called the “Nine Requirements.”

The “Nine Withs” came in Xi Jinping’s speech as he reviewed the key lines of the anti-corruption campaign as it was to continue unfolding. As the CCDI readout recounted:

Xi Jinping pointed out that in [the Party] must grasp nine issues in the deepening promotion of the Party’s fulfillment of self-revolution, namely: with adherence to the unified leadership of the CCP Central Committee as the fundamental guarantee; with the fundamental aim of leading a great social revolution; with Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for the New Era as the fundamental guideline; with the strategic goal of leaping free of the cyclical patterns of history; with a focus on resolving the challenges facing a large political party; with effective ways to improve the overall system of strict governance of the Party; with forging a strong organization and building a tough team as an important focus point; with corrective discipline and anti-corruption as an important tool; with a combination of self-supervision and people’s supervision as a strong driving force.

Immediately after the speech, Li Xi (李希), the head of the CCDI, stated these principles as a full-fledged specialized CCP phrase, or tifa (提法), telling those present that: “General Secretary Xi Jinping has clearly raised the ‘Nine Withs’ as the requirements of [our] practice.” Predictably, in the days and weeks that followed, Party-state media devoted column after column to the elucidation of this new concept in CCP discipline.

The “Nine Withs,” for all their abstraction, can be boiled down to Xi Jinping’s bald claim, and his overriding concern, for the survival of his regime.

This is evidenced immediately in the top three “withs,” which are in fact the key tenets of what are known as the “Two Establishes” (两个确立) and the “Two Protections” (两个维护). The “Two Establishes,” which emerged in the wake of the Sixth Plenum of the 19th CCP Committee in November 2021, is essentially a giftbox of loyalty to Xi, establishing him as 1) the unquestionable “core” leader of the CCP, and 2) his ideas as the bedrock of China’s future under the CCP. The phrase, once unpacked, is a claim to the legitimacy of Xi Jinping’s rule, and a challenge to any who might oppose him. Meanwhile, the “Two Protections” is about the need to 1) protect the “core” status of Xi Jinping within the CCP, and 2) to protect the centralized authority of the Party.

Anyone mindful of the crucial role of public scrutiny and external accountability in preventing corruption should immediately understand how these foundational three “withs” make real accountability impossible. They amount to the bald-faced claim that Xi’s leadership is above scrutiny.

As elaborate as it may seem, Xi’s nine-point formula for anti-corruption is staggeringly retro: an authoritarian center, consolidating power and removing barriers (such as presidential term limits), while taking up anti-corruption as a weapon to attack elements within the Party seen as problematic by the “center” — which is to say, by Xi himself.

The need to operationalize anti-corruption in the interests of regime preservation is precisely why Xi Jinping must insist that “the Party’s self-revolution is always on the road” (党的自我革命永远在路上), another key line in his speech to the CCDI conference. On the one hand, Xi must have his anti-corruption victory because failure is not an option for a party whose power is derived in large part from the manufacture of positive perceptions. On the other hand, the logic of authoritarian governance dictates that the struggle against corruption must continue relentlessly — because Xi’s power and legitimacy derive equally from the constant battle cry.

The first three of the “Nine Withs” make clear that the CCP’s “core” is primary and unassailable, and that therefore the process of anti-corruption must happen without real external monitoring. For this reason, the process of anti-corruption must be internal, about self-scrutiny and self-discipline —because any true mechanisms of accountability would mean the loss of power.

It is against this backdrop that we should understand Xi Jinping’s notion of “self-reovlution,” or ziwo geming (自我革命), which is at the heart of his wholesale recasting of the famous episode of Mao’s “Cave Dwelling Dialogue” (窑洞对) in July 1945 — from which the fourth of the “Nine Withs” is derived, focusing on the need to “leap free of the cyclical law of history” (以跳出历史周期率).

According to this well-worn narrative, Mao Zedong was asked by writer and politician Huang Yanpei (黃炎培) about how he proposed to extricate China from the constant cycle of dynastic struggles and collapse. How, in other words, could the new political order promised by Mao remain dynamic, and avoid degradation through its internal failures? Mao’s answer to Huang Yanpei’s challenge rang with confidence: “We have found a new path,” he said. “It is called democracy. As long as the public maintains their oversight of the government, the government will not slacken in its efforts.”

As elaborate as it may seem, Xi’s nine-point formula for anti-corruption is staggeringly retro.

Popular oversight is of course not the legacy Mao Zedong left behind. His decades in power were characterized by a radical over-concentration of power that drove the country from tragedy to tragedy. At the start of reforms in the 1980s, a new generation of leaders including Deng Xiaoping (邓小平) sought to prevent the over-concentration of power, recognizing the brutal excesses it had created. This included the institution of term limits of the kind that Xi Jinping has now dismantled.

Despite the CCP’s new pretensions under Xi Jinping to what it calls “whole-process democracy” (全过程民主), the promise of such democracy as might provide a real path to public oversight of the government is farther away today in China than it was 40 years ago. This is the nasty secret behind Xi Jinping’s sleight of hand in 2022, when he announced at the Sixth Plenum in November 2021 that he had a “second answer” to the “cave dwelling question” posed to Mao. That answer was “self-revolution,” he said. The Party could strictly and comprehensively — these are now the favored buzzwords — govern itself.

The “Nine Withs” is authoritarian self-governance plain and simple. Its casual mention, at the bottom of the ninth, of “people’s supervision” being combined with “self-supervision” is the most ineffectual of nods to the role of the public — as empty and meaningless as Mao’s “New Democracy,” the process of revolution he insisted “will need quite a long time and cannot be accomplished overnight.”

With the persuasive power of “self-revolution” always on the horizon of intra-party governance, thoughts of democracy, even fanciful ones, can now disappear into the past.

David Bandurski

The CMP Dictionary

C

D

F

G

M

N

P

S

- Scaling the Wall

- Science

- Second-Generation Reds

- Security

- Seeking Progress in Stability

- Seeking Truth From Facts

- Self-Revolution

- Seven Bottom Lines

- Six Adheres

- Smart Governance

- Sneaky Visit

- So-Called

- Socialite

- Soft Resistance

- Soul and Root

- Soundless Saturation / Quietly Nourishing

- Sovereignty

- Speaking Politics

- Streamlining Services

- Strong Cyber Power