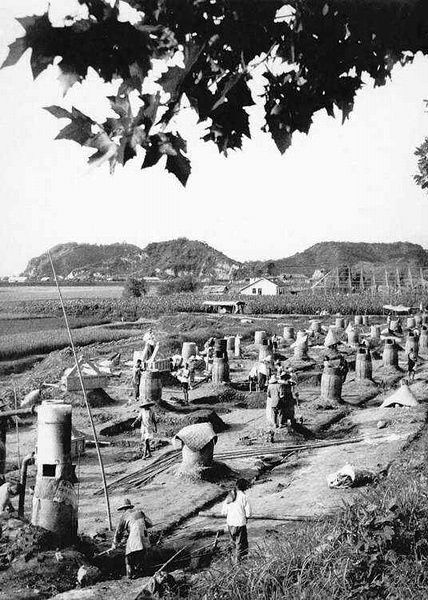

Loudspeakers look out over a village in China. Image from “Country Life” public account.

Imagine a stretch of brick village houses in the Chinese countryside, their outer walls painted with bright red propaganda posters. It’s early morning and a loudspeaker blares out local government announcements, along with the latest slogans from the top leader in Beijing.

This may sound like a scene from the height of the Cultural Revolution in the 1970s. But that’s the catch. This is the Chinese village in the second decade of the 21st century, where an old communication technology is making a comeback alongside the latest digital tools.

The shrill call of the loudspeaker, once a staple of political and economic life in pre-reform China, is a sound now returning to the countryside.

On May 6, the China Press Publication Radio Film and Television Journal (中国新闻出版广电报), the official publication of the National Press and Publication Association (NPPA), reported that more than 600 loudspeakers had been installed in a district on the outskirts of Tianjin. Promoted by the local propaganda department in Tianjin, the installation in Wuqing District (武清区) was coordinated with “Xuexi Qiangguo” (学习强国), an interactive app designed to propagate the thought of Xi Jinping along with the ideology of the Chinese Communist Party.

The shrill call of the loudspeaker, once a staple of political and economic life in pre-reform China, is a sound now returning to the countryside.

Each morning audio content from “Xuexi Qiangguo” is broadcast from the local integrated media center (融媒体中心) in Wuqing District, reaching across a digitalized “loudspeaker network” (大喇叭系统) that encompasses 611 administrative villages. The content varies every day, according to the NPPA report, and can include the theories of the Party, propaganda content hyping the upcoming 20th National Congress of the CCP – and of course quotes from Xi Jinping.

“The loudspeaker has turned into an ‘announcer’ that promotes the light of thought into the hearts of people,” the NPPA report said. The “light of thought” (思想之光) in this case was an unmistakable reference to Xi’s banner term, which this year could be shortened to the potent “Xi Jinping Thought.”

Turning Up the Volume

The loudspeaker project is not exclusive to Tianjin. According to China National Radio, the “New Rural Loudspeaker Project” (新农村大喇叭工程) has been rolled out to more than 200 cities and counties across China since it was first piloted in Shijiazhuang, the capital of Hebei province, in 2019. By the end of 2020, the project had reached an estimated 300,000 administrative villages in 14 provinces, according to a report in the official Hebei Daily newspaper.

According to state media, the project, which involves three daily broadcasts morning, noon and night, employs “internet + loudspeaker” cloud broadcasting technology. The model is pretty straightforward. The government broadcasts the messages, combining agricultural and policy content with Party propaganda, and the villagers listen.

It is a model familiar to many millions of older Chinese who lived through political movements from the 1950s through to the end of the Cultural Revolution in 1978. During those decades, loudspeakers were one of the main tools used to deliver government announcements and mobilize the population for various campaigns or movements. In 1959, in the midst of the Great Leap Forward (大跃进), a campaign to create a communist society through the formation of people’s communes, loudspeakers were used to announce quotas for grain and steel production.

A report published in the People’s Daily on February 6, 1959, related how a steel furnace in Anshan (鞍山), Liaoning province, was pressed to ever higher production levels. In the article, a worker’s representative seeks out the local Party branch chief and pledges heroically: “We guarantee that our steel furnace will generate new records, and we ask that the Party branch chief supports us!” The article then reads:

All of the loudspeakers through the factory immediately blared out: “Flat Stove No. 16 has pledged that tonight it will break its own record, breaking through yesterday’s top result! We hope all work sections will cooperate!”

During the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s, loudspeakers became a blunt yet effective propaganda tool to blare out revolutionary songs praising Mao Zedong’s leadership of the Party and bolstering his personality cult.

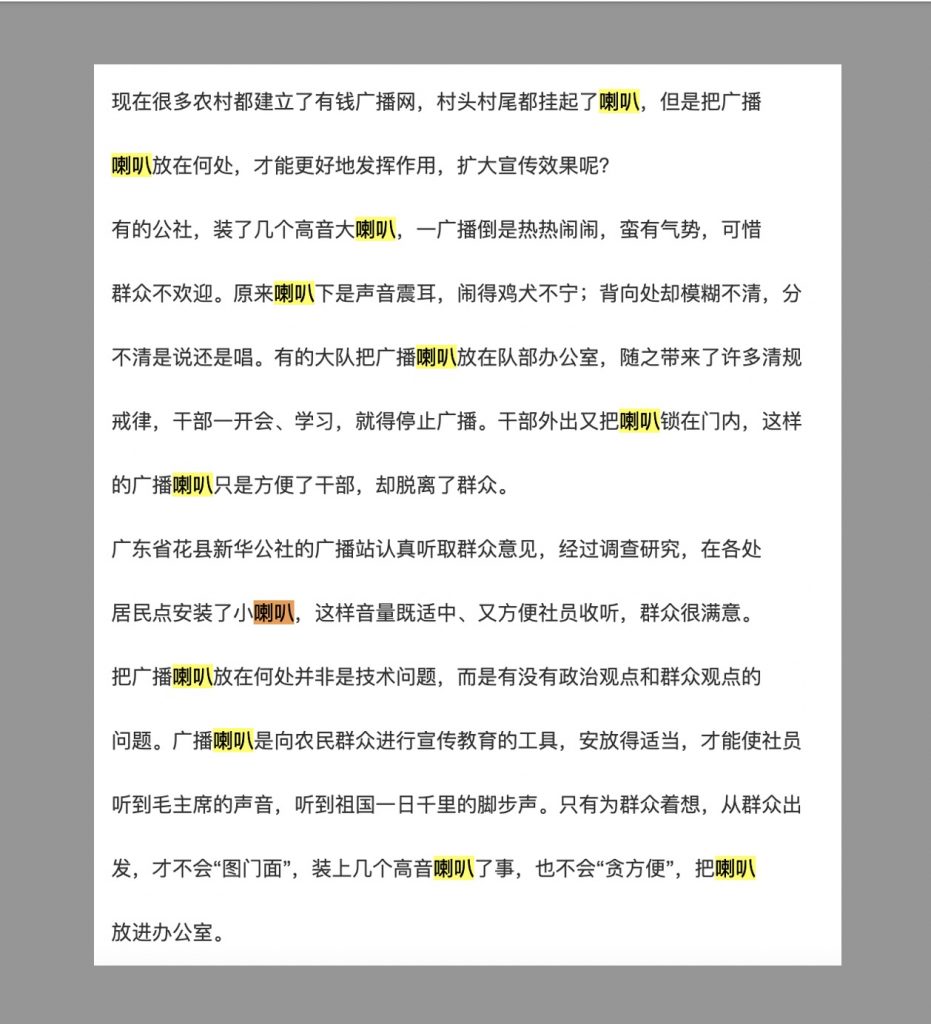

A 1965 article in the People’s Daily’s acknowledged the importance of installing loudspeakers in the countryside in order to carry out mass mobilization. But the vexing question was where to place the loudspeakers. “Where should the loudspeakers be placed in order to be more effective and have the broadest propagation result?” the article asked.

Some communes had installed several high-volume loudspeakers, but they were so cacophonous – rousing the dogs and chickens – that the masses did not welcome them. “Loudspeakers are tools for propaganda and for the education of the peasants,” the newspaper said, “and their proper placement enables members to hear the voice of Chairman Mao and the development of our country.”

Reform and Opening

As economic reforms took hold in China in the late 1970s and into the 1980s, the use of loudspeakers as tools of political mobilization largely faded. But there could still at times be a use for loudspeakers in spreading knowledge of government policies relevant to residents in the countryside, particularly up to the early 2000s, before internet access was more widespread, and years before smartphones became ubiquitous.

In 2004, as then-President Hu Jintao emphasized the need for agricultural reforms to improve the lives of China’s farmers, a priority encompassed by the so-called “Three Rural Issues” (三农问题), the People’s Daily reported about one rural village where the Party committee had decided to bring loudspeakers, “already silent for many years,” back into use in order to better advertise government policies. Twenty-five loudspeakers were installed around the village, and broadcasts were made in the morning, at noon and at night.

According to the People’s Daily report, local farmers had welcomed the installation of the loudspeakers because the broadcasts included daily announcements of the market prices of agricultural products, which helped them strike better deals with buyers.

Back to Ideology

While ideology had gradually faded in importance in China through the reform and opening period from 1978 to the 2000s in favor of Dengian pragmatism, Xi Jinping’s rise to the position of general secretary of the CCP in November 2012 brought the steady return of ideology to the center of politics. This became clear with the introduction of the hardline Document 9 in the spring of 2013, outlining “prominent problems in the present ideological sphere,” and calls in August 2013 for a re-invigoration of Marxist ideology.

Under Xi’s leadership, the loudspeaker has regained its old function, strengthening propaganda and ideology at grass-roots units – meaning at the lowest levels of the Party-state bureaucracy. In 2015, the People’s Daily reported on the mobilization in Dandong (丹东), a city in China’s northeastern Liaoning province, of a “Volunteer Army for Theory Propagation” (理论宣传志愿军). The “army” consisted of more than 10,000 members tasked with “propagating theory among the masses and arming the masses with theory” (群众宣传理论, 理论武装群众) at the village and township level.

Under Xi’s leadership, the loudspeaker has regained its old function, strengthening propaganda and ideology at grass-roots units.

The idea was to find innovative ways to transmit the voice of the Party – and increasingly, of its powerful leader. Alongside lecture events, digital message boards and public service announcements, wireless loudspeakers (无线大喇叭) offered a distinct advantage that was likely remembered by many Party officials of Xi Jinping’s generation; a way of integrating the theory of the Party with the daily lives and rhythms of the people.

The 2019 “New Rural Loudspeaker Project” (新农村大喇叭工程), introduced first in Shijiazhuang, was one of a number of initiatives across the country that integrated loudspeakers with the once-again central work of propaganda and ideology. This was happening at the same time that the “Xuexi Qiangguo” app, which Party officials and government officials across the country were often obliged to install and regularly use, was gamifying the work of ideological indoctrination – a “little red phone” for the 21st century.

When the CCP’s central leading group for study and education on the history of the Party (党史学习教育领导小组办公室) held a conference in in Jiaxing, Zhejiang province, two years ago in May 2021, officials introduced a plan to further spread the ideological lessons compiled through “Xuexi Qiangguo” by producing more than 200 audio sessions that could then be broadcast through a network of nearly 100,000 village loudspeakers. This would enable Xi Jinping’s voice, and the Party’s mainstream view of history in the year of its centennial, to reach a vast number of rural areas.

And what about that vexing question the People’s Daily had addressed on the eve of the Cultural Revolution in 1965, about the impact of the loudspeakers on quiet lives in the countryside?

In a Weibo post back in September last year, one official publication asked the public whether they felt “countryside megaphones in the New Era” (新时代的农村大喇叭) were effective or not. Some expressed support, saying they worked better than mobile phones, and that they had been key to transmitting information about Covid-19 policies. Still, there was skepticism – not just about loudspeakers, but about the comments expressing support for them.

“These comments in support must have been promoted!” one user responded. “Loudspeakers are a serious public nuisance. Loudspeakers blare out right at 7 in the morning, the decibels ridiculously high, and their advertisements are eating away at our eardrums and our hearts.”

And then there was that vexing 21st century question of legality. “But as legal citizens each of us should have the right to freely allocate our personal time, including sleep time, and we should have the right to choose what we listen to!”